Supreme Court Roundup Part One: McCutcheon v. FEC

On October 30, I participated in a presentation entitled “Supreme Court Roundup” with Ilya Shapiro of the Cato Institute. The event was sponsored by the Law School chapters of the Federalist Society and the American Constitution Society. We discussed three significant cases from the 2013-2014 Supreme Court term: McCutcheon v. FEC, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby and Harris v. Quinn. It was a spirited discussion, in which Mr. Shapiro and I presented opposing views, but I want to thank Mr. Shapiro for taking the time to visit the Law School and for sharing his perspective with the students.

On October 30, I participated in a presentation entitled “Supreme Court Roundup” with Ilya Shapiro of the Cato Institute. The event was sponsored by the Law School chapters of the Federalist Society and the American Constitution Society. We discussed three significant cases from the 2013-2014 Supreme Court term: McCutcheon v. FEC, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby and Harris v. Quinn. It was a spirited discussion, in which Mr. Shapiro and I presented opposing views, but I want to thank Mr. Shapiro for taking the time to visit the Law School and for sharing his perspective with the students.

This is the first of three blog posts on the presentation. What follows are my prepared remarks on McCutcheon v. FEC. Readers interested in Mr. Shapiro’s position on the case can refer to the amicus brief that he filed on behalf of the Cato Institute.

In McCutcheon v. FEC, the Supreme Court considered whether campaign finance laws imposing annual aggregate contribution limits violate the First Amendment of the Constitution. A plurality of the Court answered “yes,” without reaching the issue of whether limits on contributions to individual candidates also violated the Constitution. Justice Thomas concurred with the plurality opinion, but would have gone further and overruled the 1976 decision in Buckley v. Valeo, which upheld individual contribution limits. Four Justices dissented.

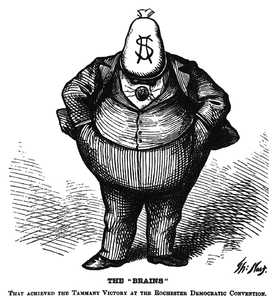

The plurality opinion in McCutcheon, written by Justice Roberts, reasoned that legal limits on aggregate contributions violate the First Amendment unless the government has a compelling interest to regulate such spending. But the only possible compelling interest available to the government is the avoidance of quid pro quo bribery, which aggregate contribution limits do nothing to prevent.

The reasoning of the plurality is not a surprise. In one sense, this reasoning is unobjectionable on the grounds that it is simply a logical application of the rationale adopted by the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), which struck down campaign finance laws prohibiting independent expenditures by corporations and unions. The problem is that Citizens United was a sharp and unjustified break with prior precedent.