Electoral College – Keep or Toss?

During the Twilight craze, the country was split between Team Edward and Team Jacob. The battle was over Bella Swan’s heart. Edward, a 200-year old vampire, was devastatingly handsome, kind, chivalrous, and his skin sparkled in the sun. Jacob, a teenage werewolf, was brash, muscular, impulsive and fiercely protective of his tribe and Bella. Oh, and Edward murdered a few thousand people but felt badly about it, while Jacob only killed vampires but had a bad mullet. I was decidedly Team Jacob.

After the 2016 election, the country is split about the Electoral College. There are again two camps: Team Keep and Team Toss. Before going into the merits of each, some brief background.

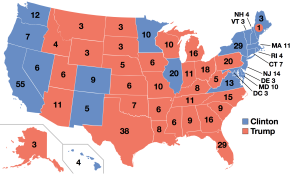

As of this writing, Donald Trump won 56% to 44% in the Electoral College (290 to 232), while Hillary Clinton leads in the popular vote count 62,523,844 to 61,201,031. So, while Trump romped to an 11-point Electoral route, he actually got clobbered by 1,322,813 votes. What gives? I thought this was a democracy.

This anomaly is the work of the venerated Electoral College. The College was created in Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution, which states in part:

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and representative to which the State may be entitled in Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

The 23rd Amendment granted at least three Electors to the District of Columbia, bringing to 538 the total number of current Electors: 435 Representatives, 100 Senators and the D.C. trio.

The Constitution does not direct how the states must “chuse” their Electors. In colonial times, most states did not call for a popular election to select their Electors. Instead, party bosses made those decisions. Eventually the cigar-smoke cleared, and today all states and D.C. hold a general election for President and Vice President, and nearly every state (48 of 50) has chosen to award all of its Electors to the winner of that state’s popular votes. Thus, because the margins in various states can differ (Clinton won California by 3.5 million votes; Trump won Florida by 20,000 votes), it is possible to win the Electoral College, and thus the keys to the White House and a cool plane, while at the same time lose the overall popular vote.

Which raises the question: is this acceptable?