The Teachings of Elections Past

Part Five of a Six Part series on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate.

Part Five of a Six Part series on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate.

In the run-up to Election Day, maps of the United States will be colored in as red or blue. This so-called “electoral map” is the focus of all the debate, particularly for the presidency, with pundits asking what color the “swing states” will shade. Of course, the maps don’t show green, purple, or even different tints of red or blue. There are only two colors, red or blue. So why is that?

Without getting too far in the weeds, as it were, and from a political science view, the shading is based on the “winner-takes-all” principle. One party wins and everyone else loses. When a party loses, that party is without representation. Weaker parties are pressured to join a more dominant party in hopes of gaining a voice. This leads to party-dominance. Voters learn that, because of party dominance, voting for a third party candidate is ineffectual to the result, and hence alignment into a two-party race between winners and losers.

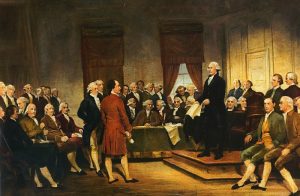

And, in terms of the presidency, by devising a system of “electors” as opposed to popular vote, history teaches us that an indirect electoral-election scheme can lead to odd results.

The elections of 1876, 1888, and 2000 produced an Electoral College winner who did not receive at least a plurality of the nationwide popular vote. What did this mean? It meant that in 2000, Al Gore received 543,895 more popular votes than George Bush, yet lost the election. The same was true for Samuel J. Tilden (New York) losing to Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876 and Grover Cleveland (New York), the incumbent President, losing to Benjamin Harrison (Indiana) in 1888.

There is also tie-breaker history. Per the Twelfth Amendment, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270) to win the presidency. If no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes in the election, the election is determined by the House of Representatives. The House chooses the President from one of the top three presidential electoral vote-winners. (A run-off vote for Vice President belongs to the Senate.)

As to a run-off presidential vote, this has happened only once since 1804.