Religious Objections to Autopsies—A Virtual Solution?

“[I]n this world,” wrote Benjamin Franklin famously, “nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Were we to add a third certainty to the list, it might be that law will have something to say about the other two. To be sure, the law has quite a bit to say about death, including a mandate, under certain circumstances, to determine the cause of one’s demise.

“[I]n this world,” wrote Benjamin Franklin famously, “nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Were we to add a third certainty to the list, it might be that law will have something to say about the other two. To be sure, the law has quite a bit to say about death, including a mandate, under certain circumstances, to determine the cause of one’s demise.

Often such determinations entail autopsies or postmortem examinations, but sometimes these examinations are offensive to the decedent’s religious beliefs or to those of surviving family members. In such situations, it has frequently been the case that the religious beliefs have had to yield to the interests of the government or the public.

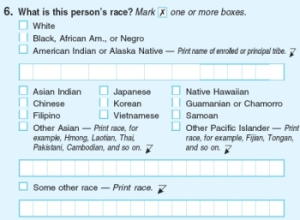

A few years ago, Kelly McAndrews (MU Law 2010) and I gave a presentation on religious objections to autopsies at a conference of the Wisconsin Coroners and Medical Examiners Association. (At the time, Kelly was the Medical Examiner for Washington County, Wisconsin.) We noted that, among other groups in Wisconsin, the Hmong and Orthodox Jews would likely have strong objections to autopsies, while that the Old Order Amish, Hindus, and some Muslims, American Indians, and Christian Scientists may have objections ranging from minor to moderate in their intensity.

Potential bases for objection, varying by religion, include: concerns about delay in the preparation and burial of the body as prescribed by religious law or tradition; concerns about the mutilation, desecration, or disturbance of the body (e.g., the body belongs to God and should not be altered, the body is needed intact for successful passage to the afterlife, or the body is needed intact in the afterlife itself); and concerns about spiritual harm to the surviving relatives for failing to take care of the decedent in a religiously proper manner.