Immediately after learning that Chief Justice John Roberts had cast the deciding vote to uphold the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, I emailed my colleague Scott Idleman and suggested that Roberts was trying to be the new Charles Evans Hughes.

Immediately after learning that Chief Justice John Roberts had cast the deciding vote to uphold the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate, I emailed my colleague Scott Idleman and suggested that Roberts was trying to be the new Charles Evans Hughes.

The reference, of course, was to Chief Justice Hughes who presided over the United States Supreme Court from 1930 to 1941. During the critical years of the early and mid-1930’s Hughes and his moderate Republican colleague Owen Roberts frequently sided with the Court’s three-man liberal bloc to uphold the constitutionality of a variety of relief statutes enacted to mitigate the harsh effects of the Great Depression. In doing so, Hughes frequently engaged in imaginative readings of supposedly settled parts of the Constitution, like the Obligations of Contracts Clause, the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Commerce Clause.

I was not the only one to make the Hughes connection. The next day, my friend Dan Ernst of Georgetown University made a similar observation on the Legal History Blog.

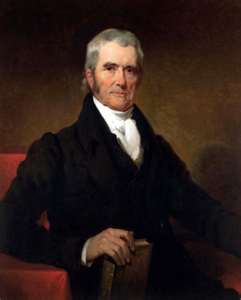

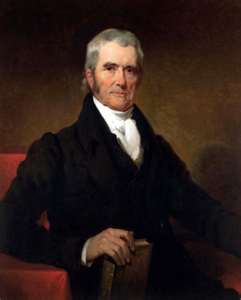

However, I have come to believe that the better comparison for Chief Justice Roberts’ Obamacare decision are the opinions of his legendary predecessor, Chief Justice John Marshall.

That Hughes failed to vote with the Four Horsemen (the name for the Supreme Court’s conservative bloc in the 1930’s) is not really surprising. He had long been associated with the Progressive wing of the Republican party, and as a member of the Supreme Court from 1910 to 1916, and as the Republican presidential nominee in 1916, he generally supported a reading of the Constitution that was consistent with progressive reform and an activist state.

Hughes sided with the liberals because he was ultimately a liberal himself. Obviously, Roberts’ relationship with the other members of the Affordable Care Act decision (National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius) was a quite different one.

The similarity between Roberts and Marshall is based upon the willingness of both to sacrifice short term results in favor of long term objectives.

Marshall did this most famously with his opinion in Marbury v. Madison (1803). While denying his fellow Federalist William Marbury his commission as a justice of the peace of the District of Columbia—a commission issued by former Secretary of State John Marshall!—Marshall was able to establish the far more important principle of judicial review in his opinion. Although Marshall’s chief adversary, President Thomas Jefferson, knew exactly what Marshall was doing, he was without recourse since his side technically won the case.

Nearly two decades later, Marshall used the same tactic to confirm the superiority of federal constitutional review over that of the state courts in Cohens v. Virginia (1821). The Cohen brothers were convicted of violating a Virginia anti-lottery statute when they tried to sell tickets for a Congressionally-authorized lottery for the District of Columbia in Virginia. Virginia courts ruled that Virginia law took precedence over the act of Congress and both brothers were fined.

The Cohens appealed their conviction to the United States Supreme Court. Virginia contested the court’s jurisdiction on the grounds that the Constitution did not give the Supreme Court appellate jurisdiction over criminal cases begun in state courts or, for that matter, over any matter involving a state as a party. Moreover, it insisted that the Eleventh Amendment immunized it from suit in federal court, including appeals to the United States Supreme Court under Section 25 of the Judiciary Act.

As in Marbury, Marshall issued a powerful defense of federal judicial authority and in doing so rejected all of the arguments advanced on behalf of his home state. However, having rejected Virginia’s constitutional argument, he then found that the statute creating the District of Columbia lottery had not authorized agents to sell tickets in Virginia, and, therefore, there was no issue of federal versus state supremacy, and the Cohens convictions were withheld.

In Green v. Biddle (1823), Marshall adopted a broad, and not at all obvious, reading of the Obligations of Contracts Clause that was clearly at odds with a strict constructionist interpretation of the Constitution favored by his Virginia opponents. However, he issued this ruling in the context of upholding the validity of Virginia land titles in the state of Kentucky (which until 1792 was the westernmost county of Virginia), again leaving his opponents with a formal victory on the facts but with a major defeat on fundamental principles.

Roberts’ Affordable Care Act opinion appears to be a decision in this line. At its core, his opinion validates the older constitutional view that the Commerce Clause places real limitations on the extent of Congressional power, even in the realm of economic regulation. This position was long believed to have been discredited by the 1942 decision in Wickard v. Filburn, but in the Affordable Care Act case (National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius) five of the nine justices endorsed such a position.

However, because Justice Roberts found an alternate constitutional basis for upholding the individual mandate provisions of the act (the tax power), liberals were hardly in a position to criticize his opinion. Instead, he was roundly praised for his willingness to work with the Court’s liberal bloc.

However, as was the case with Marshall’s Marbury, Cohens, and Green v. Biddle decisions, the full implications of Roberts’ decision will not be known until a later day. Only history will tell us if Roberts’ use of this strategy will be as effective for him as it was for John Marshall.