[The following is a guest post from Professor J. Gordon Hylton, a former member of the Marquette Law School faculty.]

[The following is a guest post from Professor J. Gordon Hylton, a former member of the Marquette Law School faculty.]

Justice Scalia’s unexpected death this past weekend has raised the question of how his seat on the Supreme Court will be filled. Some Republicans have already asserted that it would be inappropriate for the president to even place someone’s name in nomination during an election year. Others have more modestly pointed out that the Republicans in the Senate would be within their constitutional function to use their majority power to veto any potential justice that the president might put forth. Democrats, in contrast, emphasize the president’s constitutional duty to fill the slot and reject the idea that the impending election out to somehow stay the process of replacing departed United States Supreme Court rules.

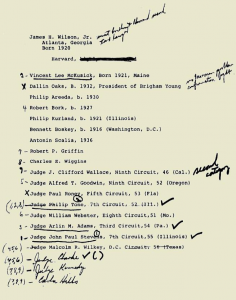

What does the history of the Supreme Court tell us about this situation? As it turns out, in the Court’s more than 225 year history, sitting justices have died or retired/resigned from the Court during an election year (or the brief stretch of the president’s term in the following year) on twenty occasions. In 14 of the 20 cases, a new justice was appointed and confirmed before the president’s current term ended. (In 7 of the 20 cases, the sitting president was re-elected, but in none of these cases did the nomination go into the following term.)

However, the story is a bit different when the sitting president’s political party does not control the United States Senate. Not surprisingly, in the 12 cases when the president’s party has been in control of the Senate, the open-vacancy has been filled 11 times. The one exception came in 1968, when sitting Chief Justice Earl Warren announced in June that he planned to retire before the end of the year.

Even though the Democrats held a 62-38 majority in the Senate in 1968, President Johnson’s nominee to replace Warren, Associate Justice Abe Fortas, soon ran into trouble as evidence of perceived financial irregularities and conflicts of interest during Fortas’ years on the Court surfaced. Ultimately, the Fortas nomination was withdrawn, and Warren remained on the Court until the following June, when newly elected President Richard Nixon nominated Warren Burger as the new Chief Justice.

In the other 8 situations, in which the President’s political party did not control the Senate, which is the current situation, the vacant court position went unfilled 5 times. In fact, that was the result the first four times the scenario presented itself. In 1828, 1844, 1852, and 1860, presidents–John Quincy Adams, John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, and James Buchanan–whose parties did not control the Senate, failed in their efforts to appoint replacements for recently deceased justices.

(Technically, John Tyler was a Whig, and the Whigs did have a slight majority in the Senate during his presidency, but Tyler’s extreme States Rights beliefs alienated a majority of his fellow Whigs. He was actually more successful in working with the Democrats in Congress. Tyler’s efforts to fulfill a previous Supreme Court vacancy created by the death of Justice Smith Thompson in 1843, which was not an election year, did not succeed until he nominated Democrat Samuel Nelson shortly before the end of his term in March 1845.)

In the four post-Civil War situations where this fact pattern appeared, Presidents had better luck, largely as the result of choosing candidates designed to appeal to their political opponents who controlled the Senate. During his presidency Republican Rutherford B. Hayes faced a Senate composed of 42 Democrats, 31 Republicans, and 2 independents. His first two nominees to the Court were chosen to appeal to the large number of Southern Democrats in the Senate by offering to restore a Southern presence to the Supreme Court that had been missing for most of the Reconstruction era. He did this by appointing former slave-holder John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky and, in the election year of 1880, William Woods, a pre-war Democrat who had been a Union general, but who after the war had relocated to Alabama where he became a cotton planter. However, when Hayes attempted to fill a third vacancy on the Court with fellow Ohio Republican Stanley Matthews shortly before the end of his presidency in March 1881, the Democratic Senate refused to cooperate.

Similarly, when Chief Justice Morrison Waite died in 1888, Grover Cleveland wanted to replace him with a Democrat, even though the Republicans held a narrow 39-37 margin in the Senate. Earlier in his tenure, his first nominee, Secretary of the Interior L. Q. C. Lamar, a former Confederate official, had been confirmed by a four vote margin, but only because a small number of western Republicans, apparently in appreciation of his policies when he ran the Interior Department, defected to his side. For Chief Justice in 1888, Cleveland nominated Illinois lawyer and Maine-native Melville Westin Fuller, apparently on the presumption that the four Republican senators from Illinois and Maine would throw their support behind their native son (which they did, and he was confirmed).

The only other time an election year nomination went through the Senate without a clear majority for the president’s party was in 1956, when Democratic Justice Sherman Minton announced on September 7, just two months before the upcoming presidential election, that he would be retiring on October 15. At this point, the Senate consisted of 47 Democrats and 47 Republicans, plus two Independents, one of whom (Wayne Morse) had recently been identified with the Republicans and one (Strom Thurmond) with the Democrats.

Even though Vice-President Richard Nixon, as president of the Senate, could cast the tie-breaking vote in the Senate divided along party lines, Eisenhower avoided a potentially costly showdown with Senate Democrats by capitalizing on a Senate recess to appoint the Irish Catholic Democrat William Brennan of the New Jersey Supreme Court to the United States Supreme Court on a temporary basis through the use of the rarely invoked interim appointment to the Supreme Court. As a result, Brennan was able to join the Court the day that Minton retired, which was three weeks before the election. (Observers then and now speculate that the decision was motivated in part by Eisenhower’s desire to appeal to Roman Catholic voters who traditionally voted Democratic.) When Brennan actually came up for confirmation in March 1957, he was confirmed by a nearly unanimous voice vote.

Consequently, the past shows that in a situation like the current one, past Senates have not hesitated to deny confirmation to the choice of an outgoing (or potentially outgoing) president. On the other hand, there have been times through clever nomination strategies that presidents have persuaded their more powerful political opponents to go ahead and support the chosen nominee, rather than gamble on a more hospitable result in the future.

It is perhaps worth noting that none of these previous situations are particularly recent. Only two of the 20 have occurred since the Election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, and of these the most recent is from 1968. Only six of the examples are from the Twentieth Century, and eight predate the conclusion of the Civil War. Nevertheless, there is no reason to think that any modern constitutional change would have produced different results or would prevent the President or the current Republican majority in the Senate to follow a similar course.

Today, the Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, announced the unprecedented decision that the United States Senate will refuse to consider any nominee put forward by President Obama during the remainder of his term in office to fill the current vacancy on the United States Supreme Court. Senator McConnell said, “My decision is that I don’t think that we should have a hearing. We should let the next president pick the Supreme Court justice.”

Today, the Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, announced the unprecedented decision that the United States Senate will refuse to consider any nominee put forward by President Obama during the remainder of his term in office to fill the current vacancy on the United States Supreme Court. Senator McConnell said, “My decision is that I don’t think that we should have a hearing. We should let the next president pick the Supreme Court justice.”