One Public Domain to Rule Them All

The Supreme Court heard oral argument this morning in Golan v. Holder, which considers the constitutionality of Section 104A of the Copyright Act, added in 1994 by the obfuscatorily named Uruguay Round Agreements Act. The constitutional issue is whether Congress can, consistent with the Copyright Clause and the First Amendment, remove works from the public domain by “restoring” copyrights to works that had either expired or failed to vest due to a failure to comply with technical requirements.

The Supreme Court heard oral argument this morning in Golan v. Holder, which considers the constitutionality of Section 104A of the Copyright Act, added in 1994 by the obfuscatorily named Uruguay Round Agreements Act. The constitutional issue is whether Congress can, consistent with the Copyright Clause and the First Amendment, remove works from the public domain by “restoring” copyrights to works that had either expired or failed to vest due to a failure to comply with technical requirements.

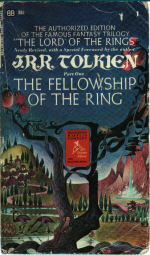

If that sounds a bit abstruse, here’s the issue put more concretely: can Congress restore the United States copyright to J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy? Or once a work is in the public domain, for whatever reason, is it there irretrievably? The first volume of The Lord of the Rings was published in the United States in 1954 with a paltry 1,500 copies; even though the Hobbit had done well, Tolkien’s publishers did not anticipate what a blockbuster success The Lord of the Rings would be. As a result, the copies soon sold out, and instead of running another U.S. printing, Houghton Mifflin, Tolkien’s U.S. publisher, imported more copies from the UK to fill demand. But apparently Houghton Mifflin screwed up, because they accidentally imported too many: U.S. copyright law at the time contained a protectionist “manufacturing requirement” for books, requiring books sold in the United States to be printed in the United States, with only limited exceptions. A paperback publisher discovered the error in 1965 and printed 150,000 copies of the trilogy without paying any royalties to Tolkien or his publishers.

The Lord of the Rings is just one example of foreign copyright owners getting tripped up by U.S. copyright formalities.