What Lakefront Reveals About the Public Trust Doctrine, Standing to Enforce Public Rights, and Possession in Property Law

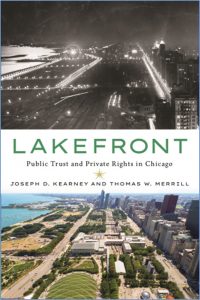

As summer began, one of my colleagues introduced readers of this blog to Tom Merrill’s and my new book, Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago (Cornell University Press 2021). The book explores how Chicago, a city known for commerce, came to have such a splendid public waterfront—its most treasured asset. Tom and I worked on the book for more than 20 years, but apparently we had more that we wanted to say. So, over the past couple of months, we gratefully accepted invitations from three national law blogs to present some reflections based on Lakefront. These posts, though drawing on, are not excerpts from the book, and each of the three series has a strong thematic element or substantive focus.

1. Volokh Conspiracy—The Public Trust Doctrine. Our first series of guest posts, appearing at The Volokh Conspiracy this past June, focused on the public trust doctrine, both in its original American conception (on the Chicago lakefront) and in its development (also there) over more than a century. We explained also that the preservation of Grant Park as an open space, in downtown Chicago, had nothing to do with the public trust doctrine, but stemmed from the public dedication doctrine. Having previously collected these posts, I include the link to that collection and thus to that series, for the sake of completeness here.

2. The Faculty Lounge—Standing to Enforce Public Rights. Our second series last month (July) at The Faculty Lounge concerned standing to enforce public rights. We began by explaining that standing in the law is nearly always discussed in terms of the Supreme Court’s doctrine governing who may sue in federal court consistently with Article III of the Constitution—and that this is unfortunate. For a wider array of standing rules comes into the picture when one considers common-law doctrines governing who may sue to enforce public rights—making Lakefront, which unpacks a century and a half of controversies over various such rights, a valuable resource.

Here is a sort of table of contents for the future reader:

- Standing to Enforce Public Rights—First of a Series (July 12, 2021)

- Standing to Enforce Public Rights: The Parens Patriae Approach (July 14, 2021)

- Models of Citizen Standing—Examined in and Through the Public Trust Doctrine (July 16, 2021)

- A Different Model of Citizen Standing: The Public Dedication Doctrine (July 20, 2021)

- Enforcing Public Rights—Federal Versus State Standing (Last of a Series) (July 22, 2021)

We concluded by urging something of an intermediate rule, given the concerns that we identified in the cases of the most restrictive standing rule (viz., underenforcement of public rights) and the least restrictive standing rule (overenforcement).

3. PrawfsBlawg—Possession vs. Ownership in Property. The third series appeared earlier this month at PrawfsBlawg. Its focus was the role of possession in property. We framed the central question thus: “In particular, the book documents a number of episodes in the history of Chicago (its lakefront, that is) in which someone either was in possession of some resource but had no clear right of ownership or, by contrast, had a fairly clear legal right of ownership but lacked possession. Who was more likely to prevail: the possessor without ownership, or the owner without possession?”

Here is the table of contents, if you will, to this third five-part series:

- Possession vs. Ownership in Property—First of a Lakefront Series (August 5, 2021)

- What Does the Public Dedication Doctrine Show Us About the Importance of Possession in Property? (August 9, 2021)

- The Power of First Possession in Property (August 13, 2021)

- Boundary-Line Agreements and Possession: The Extraordinary and Ordinary Story Behind Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive (August 16, 2021)

- Possession as Estoppel—Last of a Lakefront Series on Property Law (August 19, 2021)

With respect to the substance of this series, suffice it to say here that, at least on the Chicago lakefront, courts have been reluctant to interfere with possession—and further, in its absence, often have been reluctant to uphold seemingly strong legal claims of property rights. There is, necessarily, much history along the way, including versions of the stories of Cap’n Streeter and of how Jean Baptiste DuSable Lake Shore Drive (as Lake Shore Drive was renamed this summer) came to be—and why it stops where it does.

* * * *

To be sure, my summer was largely spent in administrative work, but I continue very much to believe in the usefulness of blog posts to foster intelligent discussion and engender learning about the law, as I suggested in one additional post that I smuggled into The Faculty Lounge. I hope for a great academic year to come on this blog.