Although the fact went largely unnoticed, the May 2011 Law School Commencement marked the centennial anniversary of the first real law degrees awarded by Marquette University. In June of 1911, nine students who had entered the initial full-time law program offered by Marquette University in the fall of 1908 received their bachelor of laws diplomas at the annual Marquette Commencement ceremony.

The subject of early Marquette law degrees is complicated by the decision of the University to award Marquette Law degrees to all the former students of the Milwaukee Law School (which Marquette acquired in 1908) who had passed the Wisconsin bar examination. The decision was apparently made at the last minute, and few documents pertaining to the decision survive. (It is, for example, hardly mentioned in the Trustee minutes.) Apparently the decision was also intended to apply to former Milwaukee Law School students who were enrolled at the time of the “merger” and who continued on in the new night program at Marquette.

As a consequence, more than 80 law degrees were awarded in 1908, before the new law school actually began operations, and additional degrees to former Milwaukee Law School students were awarded at the next several commencements. This decision later came back to haunt the law school, as critics (especially faculty members of the University of Wisconsin Law School) later accused the school of “selling diplomas.” (Degrees were not automatically awarded to former Milwaukee Law School students who passed the bar examination; they first had to apply to Marquette for a degree and pay a $5 diploma fee.) In response, the degrees awarded to the Milwaukee Law School students were soon re-labeled “honorary degrees.”

However, by the spring of 1911, there were students who had completed all of the requirements of the new full-time, day-only law program at Marquette. A class picture of these students now hangs in the hallway of the Dean’s suite in Eckstein Hall. (The composite photograph actually shows 11 members of the graduating class, when in fact only 9 actually graduated. The photograph was apparently prepared before the end of the Spring 1911 semester and circumstances apparently kept two of the 11 from graduating. Things like that do happen.)

The 1911 Commencement was held at 8 p.m. on the evening of June 21, 1911, in the Pabst Theater. Music was provided by the Marquette University Orchestra and the Marquette University Mandolin Club, and the event was presided over by Marquette President James McCabe, S.J.

The 1911 Commencement had a distinctively “legal” flavor (in part because the Marquette Medical College and its affiliated programs held their own separate graduation ceremony). The Commencement address was delivered by Patrick H. O’Donnell, a prominent Chicago lawyer and graduate of Georgetown law school who was instrumental in the creation of the law school at Loyola of Chicago the following year.

The only honorary doctorate awarded that day was a Doctorate of Laws degree awarded to the Rev. Antoine Ivan Rezek, the author of the recently published “The History of the Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie and Marquette.” (Why Father Rezek was awarded a Doctor of Laws degree rather than a Doctor of Arts is not clear.)

Of the 29 actual degrees awarded, 18 were in the field of law. Of the non-law students, Luis Rivera, a citizen of the Philippines, received a Master of Arts degree. Nine students received the Bachelor of Arts degree while a tenth received the degree of Bachelor of Science.

As mentioned above, nine graduates were awarded the Bachelor of Laws degree for work done in the day division, while an additional nine were awarded “the Honorary Degree of Bachelor of Laws” for work done either at the Milwaukee Law School or in the Marquette evening program and for passing the Wisconsin bar examination. Because the next administration of the bar examination was not until July, none of those students who had finished the night course in June of 1911 were eligible for degrees.

(In 1911, any person who had studied law for three years was eligible to take the Wisconsin bar examination regardless of whether or not they had a law degree, and the diploma privilege would not be extended to Marquette degree holders for another two decades.)

Only one of the first nine “true” graduates—Albert O’Melia—graduated with honors, but there was obviously a great honor simply in being a member of the inaugural graduating class. A more detailed account of the law school experiences of the Class of 1911 can be found in my earlier blog post entitled “The First Joe Tierney’s Marquette Legal Education.”

[Update: a reference in the fourth paragraph was corrected to read “1911” instead of “2011.”]

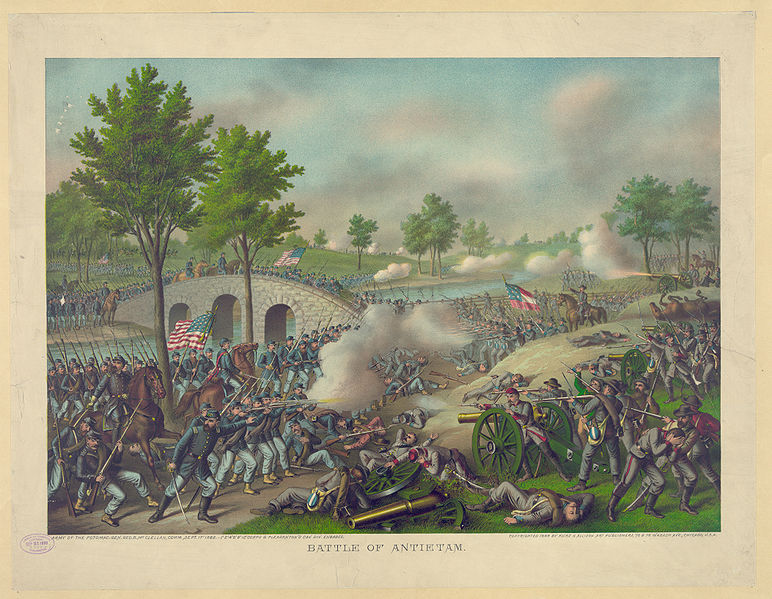

By June 1863, the Confederates had won some major victories at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, although they paid a heavy price with the loss of the legendary Stonewall Jackson. Tragically, he was killed by some jumpy Confederate pickets who had mistaken him and his troops for Northerners.

By June 1863, the Confederates had won some major victories at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, although they paid a heavy price with the loss of the legendary Stonewall Jackson. Tragically, he was killed by some jumpy Confederate pickets who had mistaken him and his troops for Northerners.