One of the many unusual features of the Electoral College established by Article II, Section 1, of the United States Constitution is the provision that specifies that each state shall have “a Number of Electors equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”

One of the many unusual features of the Electoral College established by Article II, Section 1, of the United States Constitution is the provision that specifies that each state shall have “a Number of Electors equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”

The one obvious consequence of this provision is to enhance the influence of the smaller states in the selection of the president. Because of this provision, smaller states are disproportionately represented in the Electoral College. For example, the 12 smallest states today—Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming together account for only 17 (of 435) representatives in the House, or 3.9% of the total. However, in the Electoral College, thanks to the “Senate bump,” the same states account for 41 electoral votes, or 7.6% of the total of 538.

Would the history of American presidential elections have been different, had this non-democratic element not been added to the Electoral College formula in 1787? What if Electoral votes were calculated only on the basis of the number of representatives in the House of Representatives? Have some presidential candidates been elected only because they captured the electoral votes of a disproportionate number of small states?

It turns out that the answer to the last question is yes, although the results of only three of the fifty-six presidential elections have been effected. Not surprisingly, the three affected elections are also the three closest in American history.

The first was the Hayes-Tilden Election of 1876. Widespread voter intimidation and corruption in the South made it impossible to determine which of the conflicting returns from South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana were accurate, and Congress ended up establishing a special Election Commission composed of Senators, Representatives, and Supreme Court justices to sort out the mess. Apart from the merits of the Commission’s decision, the official count produced the closest finish in history, with Hayes edging Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185-184. However, Hayes carried 21 states to Tilden’s 17. Had it not been for the assignment of two additional electoral votes to each state, Tilden would have prevailed, the rulings of the Electoral Commission notwithstanding, 150-143.

The second affected election occurred in 1916 when Democrat Woodrow Wilson ran for reelection against Charles Evans Hughes who stepped down from the Supreme Court to run for president. In an election in which Wilson’s slogan was the ironic “He kept us out of war,” Wilson edged Hughes by a margin of 23 electoral votes, 277-254. In sharp contrast to the late twentieth and twenty-first century pattern, the Republican Hughes’ support was concentrated in urban areas in the North and Midwest, while Wilson was strongest in the smaller states of the West and South. Wilson ended up carrying 30 states to Hughes’ 18, and if the two additional votes were to be subtracted for each state, Hughes would have prevailed 218-217.

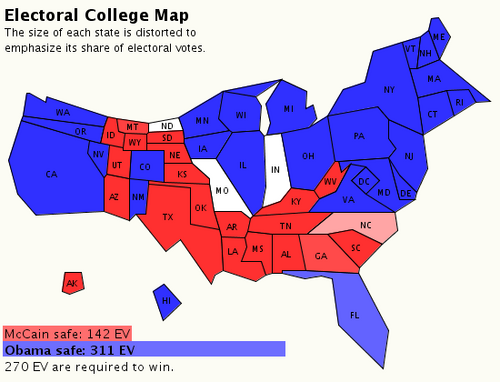

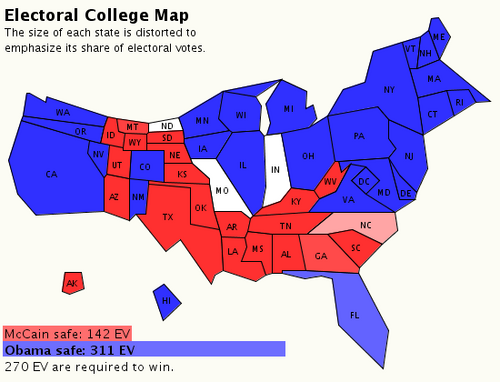

The third election was the 2000 presidential election in which George W. Bush defeated Al Gore, albeit not without great controversy, by a margin of 271-266 electoral votes. (The total electoral vote was 537 because one Gore elector refused to cast his ballot.) As in 1916, but with the parties switched, Bush carried most of the smaller states while Gore’s support was stronger in the larger, more urban states. With the two electoral vote bump removed, Gore would have won 225-211.

If we view the “Senate bump” in the Electoral College as undesirable, nothing short of a constitutional amendment can completely remove it. A dramatic increase in the size of the House of Representatives, which is within the power of Congress, could have almost the same effect, in that the value of the extra two votes would be minimized, if there were, say, 870 members of the House of Representatives rather than 435. However, a much larger House of Representatives does seem to be an item on anyone’s political agenda.

That the Electoral College with its strange features has survived for more than two centuries (and with no modification since 1804) is more than anything else a tribute to the stability of American politics and the narrowness of the American political spectrum. Compared to most European countries, the left and the right in American politics are so close together that presidential elections usually have little real effect on the direction of the country. The Electoral College may produce an occasional unfair result, but so far the consequences of the unfair results have not been significant enough to inspire a large numbers of Americans to demand change in the current system.

One of the many unusual features of the Electoral College established by Article II, Section 1, of the United States Constitution is the provision that specifies that each state shall have “a Number of Electors equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”

One of the many unusual features of the Electoral College established by Article II, Section 1, of the United States Constitution is the provision that specifies that each state shall have “a Number of Electors equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.”