Capital Punishment and the Contemporary Cinema

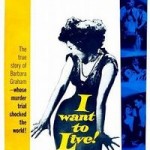

American cinema of the last century includes a large number of films with major characters on death row. James Hogan’s silent film “Capital Punishment,” for example, screened in 1925. During the 1950s, the death penalty was at the forefront in such respected films as Fritz Lang’s “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt” (1956), Robert Wise’s “I Want to Live” (1958), and Howard Koch’s “The Last Mile” (1959). The late 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century saw an even greater number of films inviting contemplation of the death penalty.

American cinema of the last century includes a large number of films with major characters on death row. James Hogan’s silent film “Capital Punishment,” for example, screened in 1925. During the 1950s, the death penalty was at the forefront in such respected films as Fritz Lang’s “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt” (1956), Robert Wise’s “I Want to Live” (1958), and Howard Koch’s “The Last Mile” (1959). The late 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century saw an even greater number of films inviting contemplation of the death penalty.

The latter flurry of films perhaps relates to the period’s especially pronounced campaign to end capital punishment. In keeping with the often-heard assertion that Hollywood leans to the left politically, most of these films seem opposed to the death penalty. Some express their opposition in the fashion of a “message film,” while others proffer more subtle dramatic narratives.