I had the opportunity in August to spend a day at the Litchfield Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut. Although several universities enrolled students in law departments during the final decades of the eighteenth century, almost all lawyers of the period prepared for practice by completing apprenticeships in lawyers’ offices. Attorney and Judge Tapping Reeve thought that education at a formal law school would be a better way for lawyers to prepare, and therefore he founded the Litchfield Law School in 1774.

I had the opportunity in August to spend a day at the Litchfield Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut. Although several universities enrolled students in law departments during the final decades of the eighteenth century, almost all lawyers of the period prepared for practice by completing apprenticeships in lawyers’ offices. Attorney and Judge Tapping Reeve thought that education at a formal law school would be a better way for lawyers to prepare, and therefore he founded the Litchfield Law School in 1774.

More than 1,100 students attended the Litchfield Law School before it closed in 1833. Two of Reeve’s students (Aaron Burr and John C. Calhoun) went on to become Vice President. Fifteen of the students became governors. Three of the students became Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. Twenty-eight students became United States Senators, and another ninety-seven served in the United States House of Representatives. Clearly, the Litchfield Law School was important in educating and credentialing a significant portion of the era’s most accomplished lawyers.

It took students two years to complete the full course of study at Litchfield, and all classes met in a small, one-room building that Reeve had constructed specifically as the School. Lectures covered a range of subject areas including contracts, domestic relations, evidence, and property, and a moot court took place weekly. Visitors to the School can review the surviving notebooks of several students. I consulted one notebook which began with a still-timely discussion of what counts as a “right” under the law.

Overall, Reeve and his eventual partner Attorney James Gould strove for a comprehensive study of law, including more than the reigning common law. Reeve and Gould expected students to recognize law’s complexities and complications and hoped the students would develop a theoretical understanding of the law. Having acquired a rich appreciation of the law, students went on to be leaders of the era’s bar and especially distinguished themselves in public service.

It might be worth remembering the Litchfield Law School’s goals and achievements in the present, when some urge that law schools tend more to training rather than to educating their students. Yes, internships and clinical experiences are increasingly valuable parts of legal education, but law schools should still emphasize the comprehensive, theoretical understanding of the law. Our goal, after all, is not merely the production of lawyers but rather the graduation of men and women who will become great lawyers. Tapping Reeve figured out a way to accomplish that at the Litchfield Law School in the 18th century, and his model of legal education remains worthy of emulation.

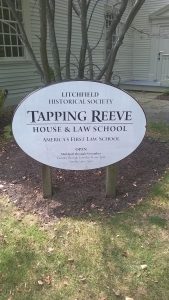

Pictured below: the Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut.