In 1776, as the founders were meeting to form the new government for the nation that would become the United States of America, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John Adams and asked him “to remember the ladies” while drafting the governing documents. She continued,

In 1776, as the founders were meeting to form the new government for the nation that would become the United States of America, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John Adams and asked him “to remember the ladies” while drafting the governing documents. She continued,

[B]e more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors [have been]. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of husbands. . . . [I]f particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.

Quoted in Susan Gluck Mezey, Elusive Equality: Women’s Rights, Public Policy, and the Law 5 (2011) (internal citations omitted).

John Adams responded, “I cannot but laugh . . . .” Id. To Mr. Adams, this was the first he’d heard of women’s possible discontent with the status quo. “[Y]our letter was the first intimation that another tribe, more numerous and powerful than all the rest were grown discontented.” Id. For whatever “power” that Mr. Adams suggested that women had, it clearly wasn’t enough, for the new Declaration of Independence and Constitution failed to give any express (or even implied) rights to women.

Mrs. Adams responded to her husband, “I cannot say that I think you are very generous to the ladies; for whilst you are proclaiming peace and good-will to men, emancipating all nations, you insist on retaining an absolute power over wives.” Id.

Abigail Adams’ caution about a rebellion in fact came to pass. During the first wave of feminism in the mid-19th century, early feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony lobbied for myriad social and civic rights for women. The 1848 Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, modeled after the Declaration of Independence, proclaimed, among other things, the “fact” that man “has compelled [woman] to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice [and that h]e has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men—both natives and foreigners.”

Nonetheless, despite their lobbying, women’s voices were still ignored. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, provided that the right of “citizens . . . to vote shall not be denied or abridged . . . on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude”; the wording expressly left out “sex,” thus still depriving half the population of the right to vote. (Read here and here how the move to enfranchise African American men but no women of any race or color divided the women’s movement.) It wasn’t until 1919 that women finally secured that right with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, ratified in 1920. But obtaining the right to vote was just one right. An important right, to be sure, but many women believed the right to vote should not be the only express right the Constitution should provide them.

In 1923, Alice Paul introduced an equal rights amendment. That amendment expressly granted to women equality of rights under the law. It was introduced every year in Congress and never passed. The wording of the amendment was later revised to its current form, which states as follows:

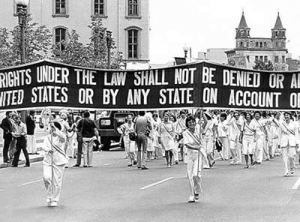

Section 1. Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

With the resurgence of the women’s movement in the second wave of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s, support for an equal rights amendment grew. The amendment finally passed both houses of Congress in 1972 and within a year was ratified by 22 of the 38 states needed to make it official. By 1977, 35 states had ratified the amendment, leaving it three states shy of enactment. Congress extended the deadline for ratification until 1982, but no other states ratified it.

Some attribute the amendment’s failure to the feminism backlash that began after the United States Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). Opponents argued all sorts of doomsday scenarios that would occur if the amendment were to be ratified: women would be sent into combat, abortion rights would be made constitutional, gays would be allowed to marry (because the amendment wording said “sex”), women would no longer have a right to be supported by their husbands, and unisex bathrooms would become required. See, e.g., here and here.

The amendment continues to be introduced yearly. Recently, a group has created a petition on the White House website, petitioning the Obama Administration to support the ERA and to push to eliminate the deadlines imposed on the 1972 amendment. In order for the Obama administration to review the petition, the petition must first garner 25,000 signatures in 30 days. The 30-day deadline is February 10, 2013, and as of early February 1, 2013, the petition had just over 15,000 signatures.

Why would an equal rights amendment still be needed? Many of the concerns opponents had raised are no longer valid; such events transpired even without an equal rights amendment. That is, the ban on women in combat has been lifted and a number of states have allowed gays to marry. The federal government has abandoned its defense of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and President Barack Obama specifically supported the right of gays to marry in his second inaugural address.

Since 1973, though, abortion rights have slowly constricted with each new case to come to the United States Supreme Court and opposition to those rights (and certainly to expanding them) shows no signs of slowing down. In the past year, many states have introduced if not enacted legislation that place significant or burdensome restrictions on those rights. While Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has allowed women (and men) to sue for sex/gender discrimination in the workplace, such suits are hard to win. Given the high burden placed on plaintiffs to prove discrimination and the statutory prerequisite that to be covered by Title VII an employer have a certain number of employees, Title VII turns out to be either inapplicable or not amenable to an employee’s case.

Where a discrimination claim is based not on Title VII but on the Fourteenth Amendment equal protection clause, courts use only a heightened standard of review, determining whether the law serves important governmental interests and whether the gender classifications are substantially related to meeting those important interests. Again, such suits tend to be difficult to win because there is often very little overt gender discrimination written into laws anymore; courts require the government to have acted with a clear discriminatory intent. And not all members of the United States Supreme Court believe that the Fourteenth Amendment provides any protection whatsoever for sex discrimination.

As I stated earlier, what makes constitutional protection so important is that once such a right is inscribed into the founding documents that right becomes more fundamental, harder to eliminate. Rights granted by statute or court decision do not always remain in place; a different Congress, a different Court—either of them may undo what has been done, swiftly removing rights or protections once granted. Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln makes this same point about the Thirteenth Amendment. As Lincoln attempts to explain why the Thirteenth Amendment is so important to pass, he notes his 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and his concern about it being legal.

I felt right with myself; and I hoped it was legal to do it, I’m hoping still. Two years ago I proclaimed these people emancipated – “then, hence forward and forever free.” But let’s say the courts decide I had no authority to do it. They might well decide that. Say there’s no amendment abolishing slavery. Say it’s after the war, and I can no longer use my war powers to just ignore the courts’ decisions, like I sometimes felt I had to do. Might those people I freed be ordered back into slavery? That’s why I’d like to get the Thirteenth Amendment through the House, and on its way to ratification by the states, wrap the whole slavery thing up, forever and aye. As soon as I’m able. Now.

I do not know whether Lincoln himself actually said those words. But the point he made is important: a constitutional amendment is more powerful than other decrees.

Enacting an equal rights amendment would clearly provide both women and men with protection against discrimination based solely on their gender and laws enacted based on stereotyped notions about what each gender can and should do or how each should behave. It would likely require that the United States Supreme Court treat gender as a suspect class, much like race, applying strict scrutiny, which asks whether the law serves compelling state interests and if that law is necessarily related to those interests. If there ever comes a day when our government is run primarily by women—right now, only 18.3% of Congress, 33% of the United States Supreme Court, and 36% of President Obama’s first cabinet is female and no woman has ever been elected president—men can be assured that the majority in power do not enact laws discriminating against them. See here for more reasons why an equal rights amendment is needed.

But maybe most of all, enacting such an amendment will show to the world that the United States really and truly is what it purports to be: a place of equality for all.

Well written! Bravo to Mrs. Adams, and to all those women and men that had (have) such insight.