This post is part 1 of a 3-part series based on data originally presented at the first Milwaukee Area Project conference. Part 2 focuses on commuting and migration. Part 3, considers the future of the Milwaukee area workforce.

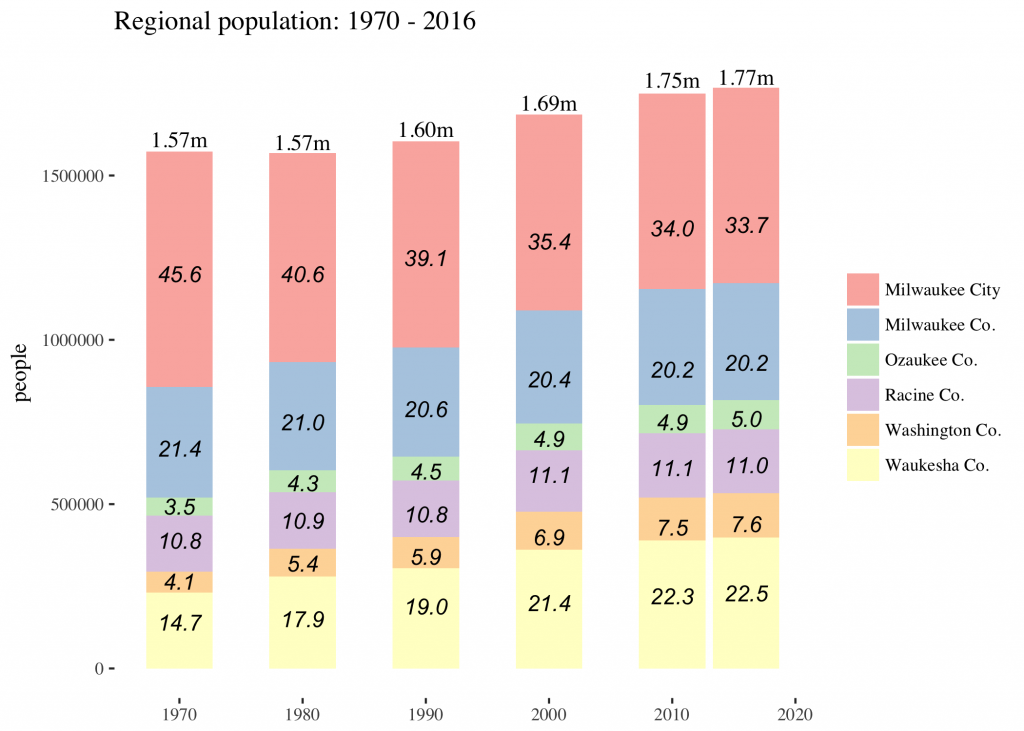

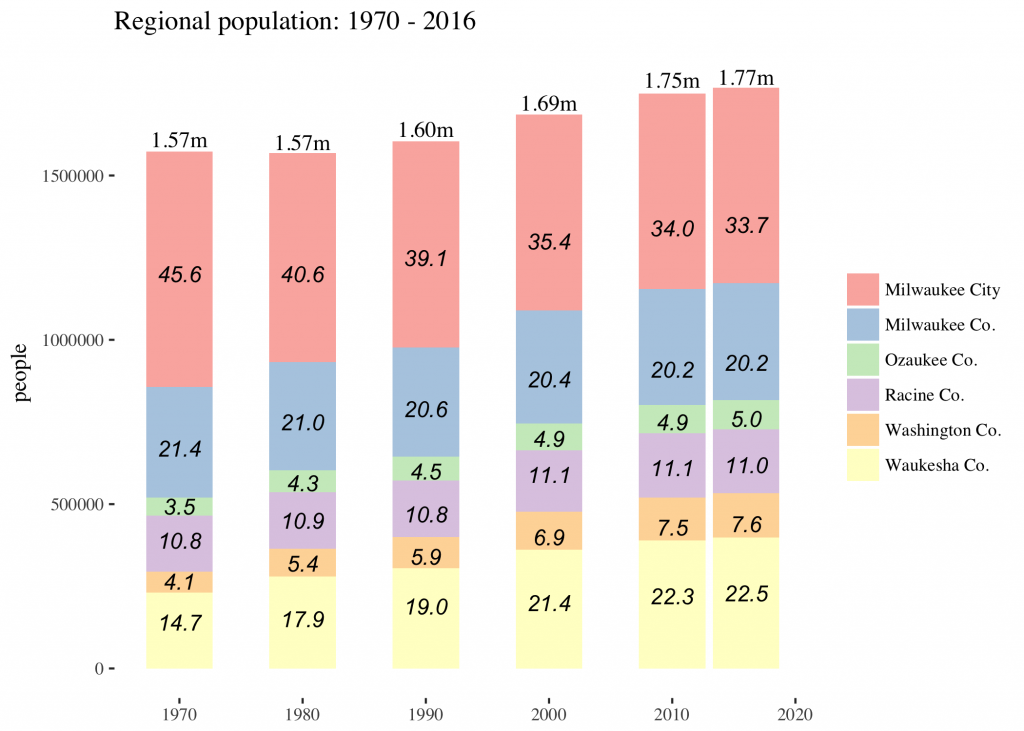

Over the past few decades, the Milwaukee area has evolved from a traditional central city and suburban dichotomy to a more evenly balanced multi-polar region. In 1970, about 46% of the entire five-county region lived within Milwaukee City limits and two-thirds lived within Milwaukee county. Today, the county’s share of the population has fallen to 54%. Milwaukee City is still more populous than any “suburban” county, but Waukesha, Washington, and Ozaukee have all grown significantly.

The most robust recent gains have occurred in Waukesha and Washington counties, both of which enjoyed double-digit growth rates from 2000 to 2016. Washington county added 17,800 new residents and Waukesha 37,700.

Over the same period the city of Milwaukee lost about 1,900 people—although this 0.3% decline represents a major improvement over the previous decade, which saw the city drop by more than 31,000 residents. Among incorporated municipalities, Waukesha city gained the most (7,500), with Oak Creek just behind (7,400). The largest losses came in Racine (4,300), followed by Milwaukee and West Allis (1,200).

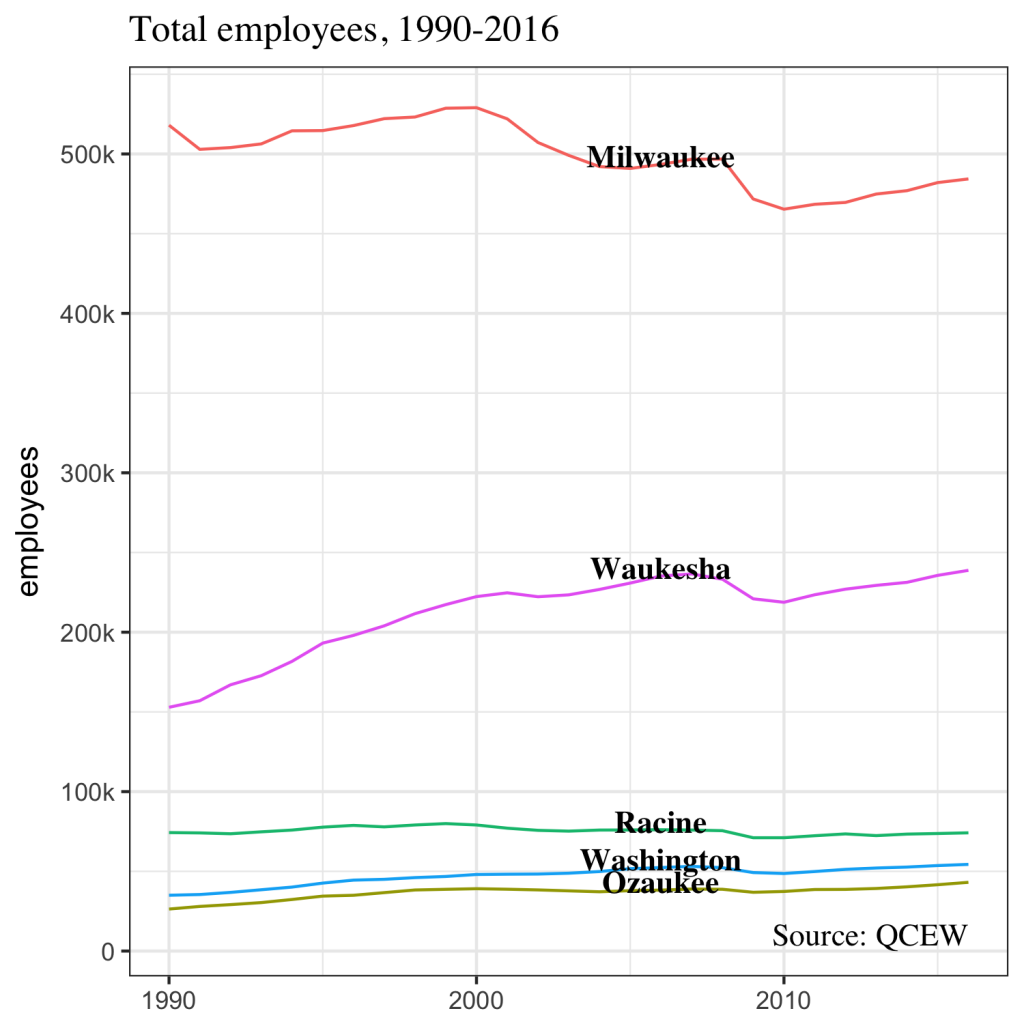

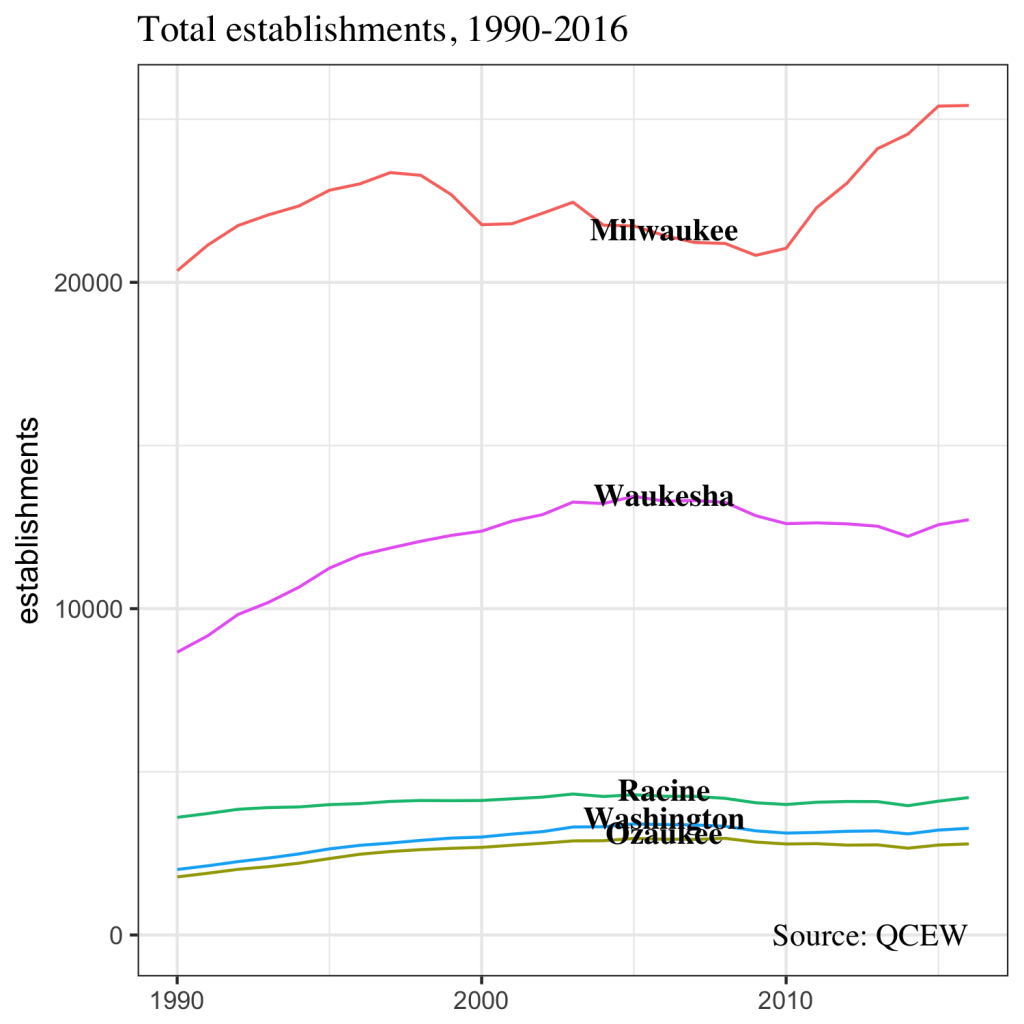

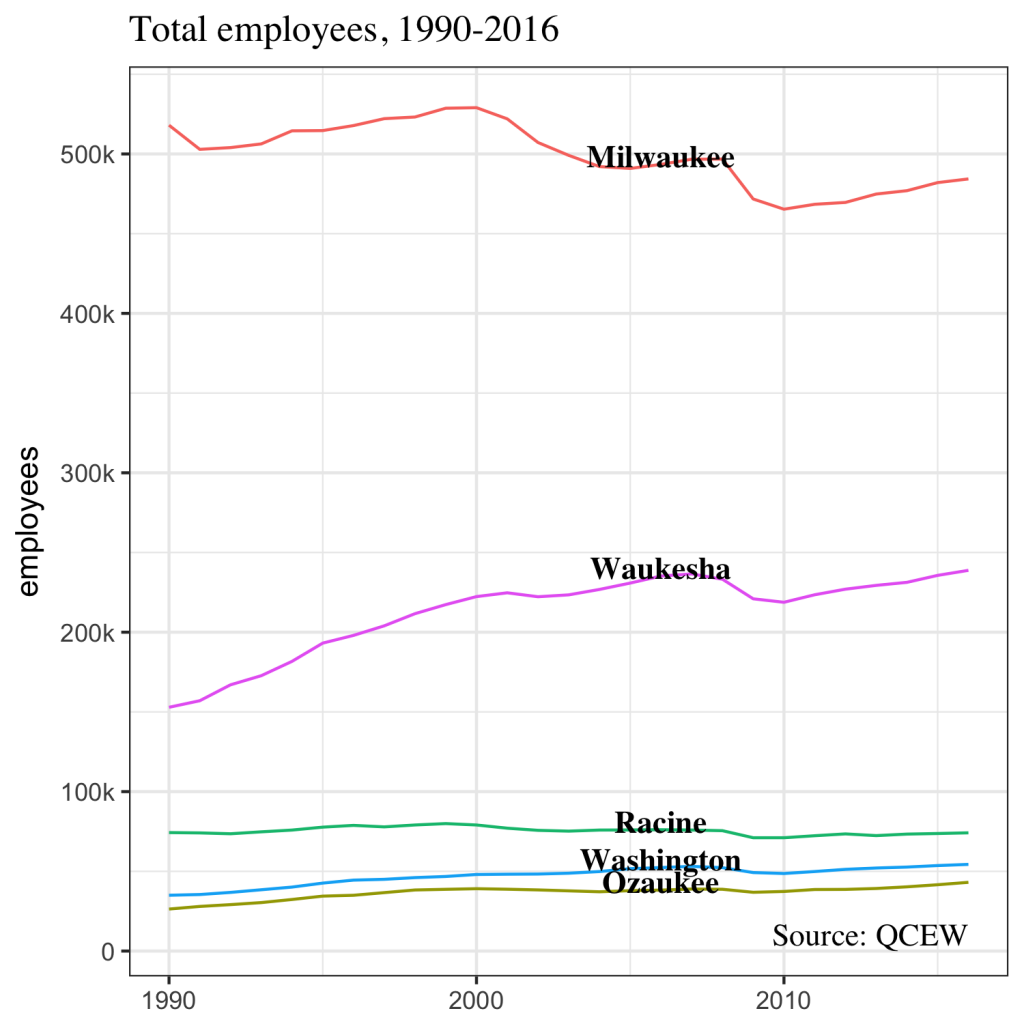

Total employees over the years tells a similar story. (This refers to total jobs in the county, regardless of where the workers live). In 2016, the 5-county region hosted 895,000 jobs. Fifty-four percent of these positions were located in Milwaukee county, while 27% were in Waukesha.

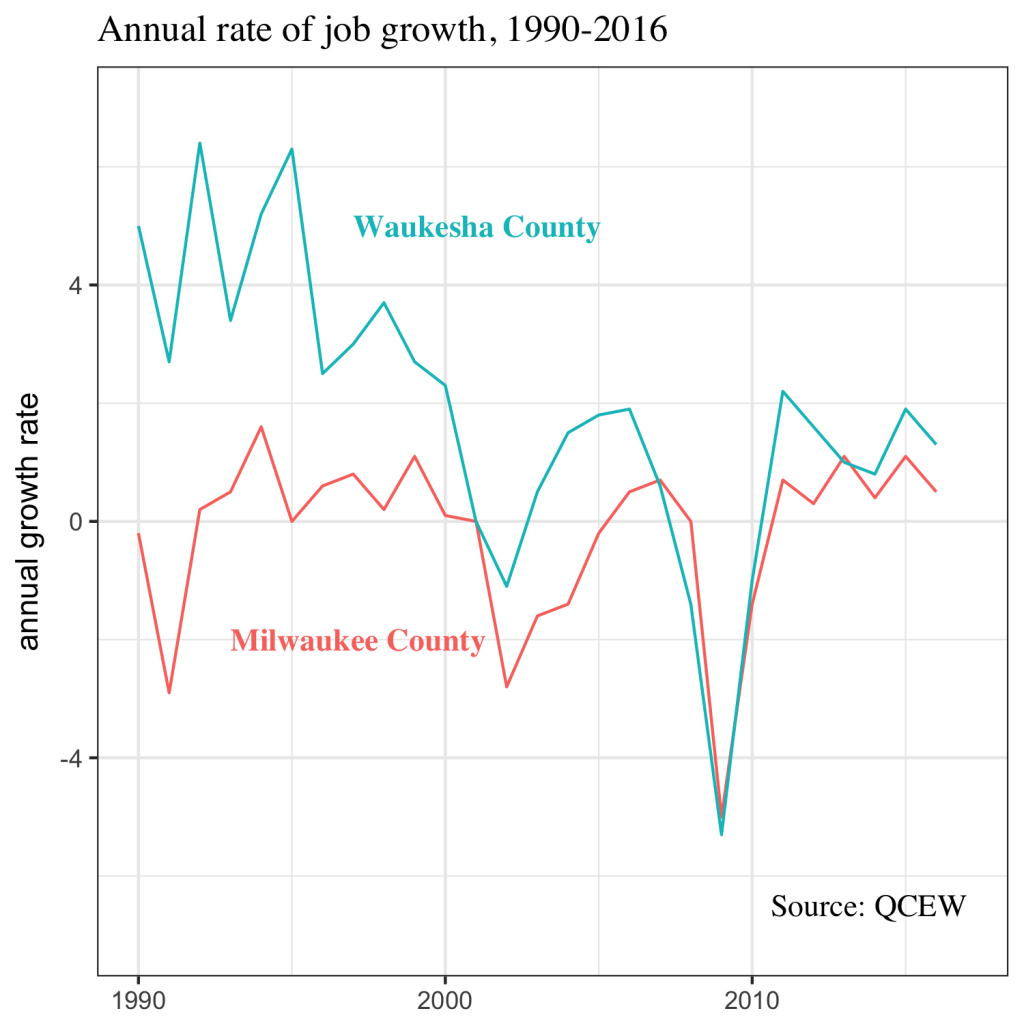

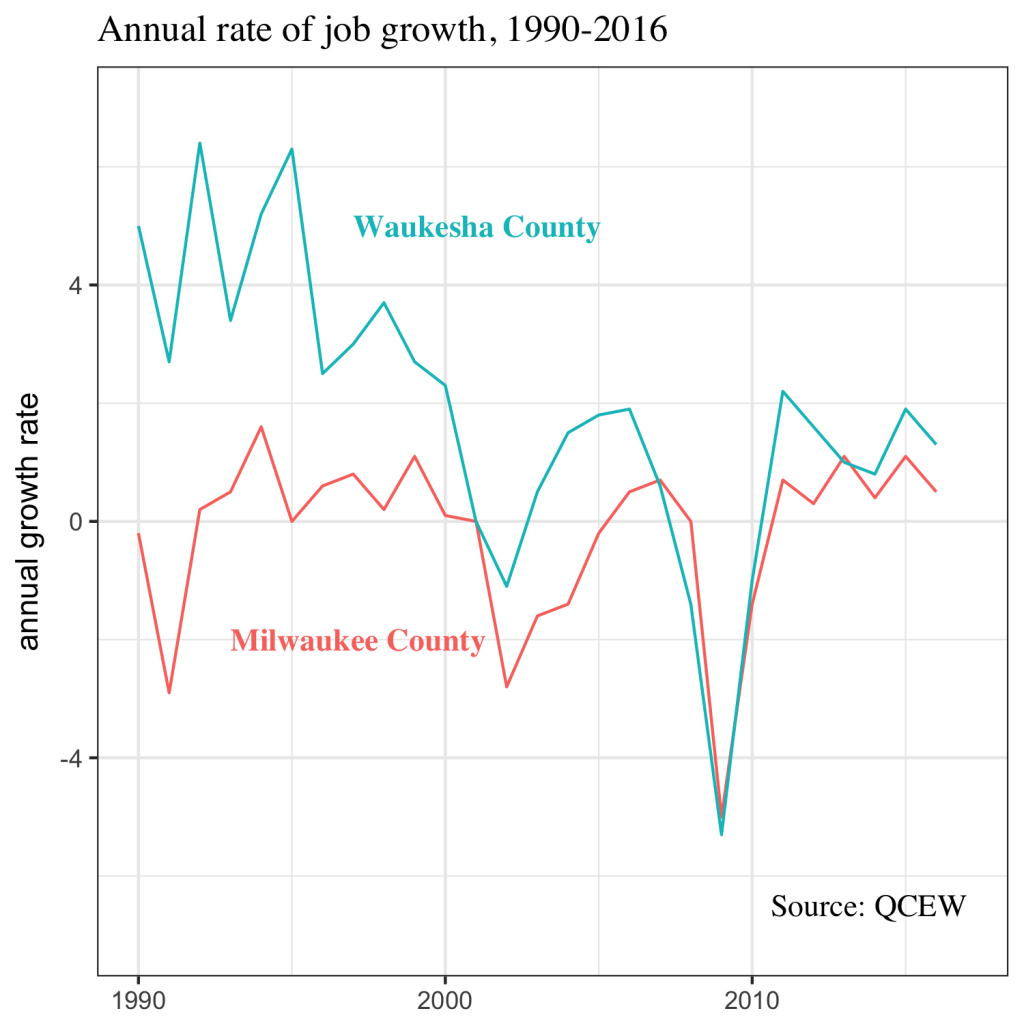

During the 1990s Waukesha county added jobs at a robust average pace of 4.1% a year. Milwaukee county’s growth was much more anemic— an average of just of 0.2% annually. Likewise, the national economic downturn in the early 2000s affected the two counties in very different ways. From 2000 to 2007 Waukesha’s job growth merely slowed to an annual pace of 0.9%, while Milwaukee’s labor force contracted—declining an average of 0.6% each year.

These differences between the two counties have been less apparent since the Great Recession. Both counties fell hard. Milwaukee lost 6.3% of its workforce from 2007 to 2010, and Waukesha lost 7.5%. Since then, they have recovered in a similar fashion. During the 2010s Waukesha’s average annual growth rate has been 1.1% and Milwaukee’s has been 0.4%. In raw terms Milwaukee added 19,000 jobs from 2010 to 2016; Waukesha added 20,000.

The Milwaukee Area’s smaller counties have also recovered steadily from the Great Recession. Since 2010 Racine has averaged 0.6% annual job growth, Washington 1.4%, and Ozaukee 2.3%.

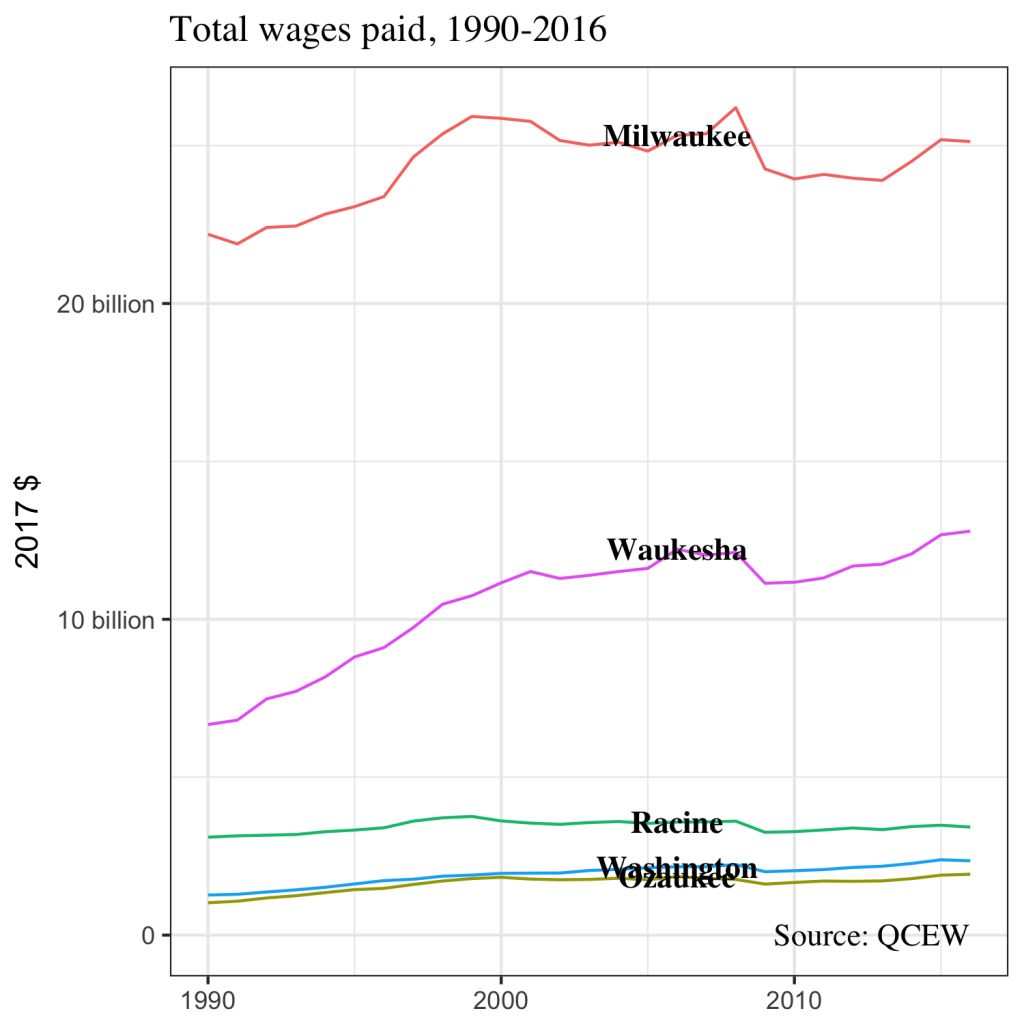

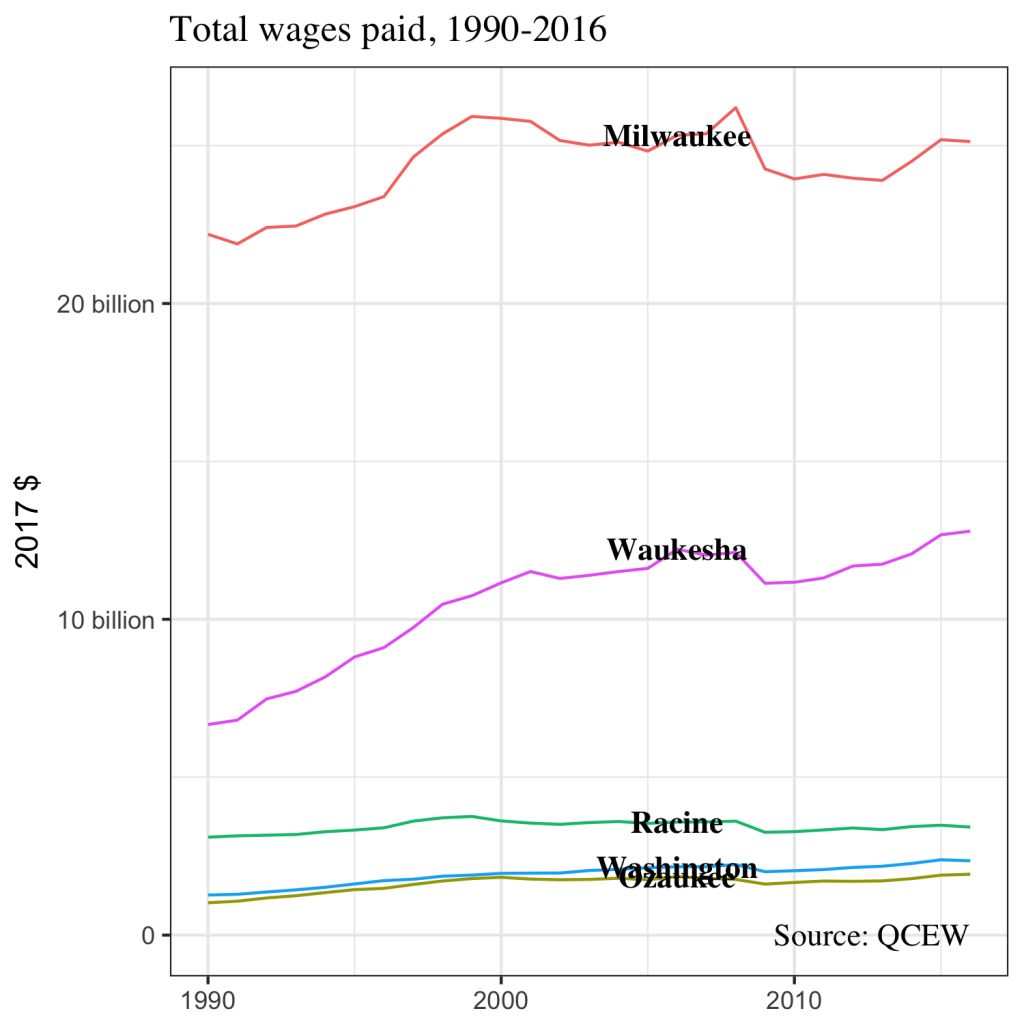

Workers in the entire five-county Milwaukee Area earned about $45.6 billion in 2016. Milwaukee county earners brought home 55% of this. Waukesha employee’s earned 28% of the total. Racine, Ozaukee, and Washington counties combine for the remaining 17%.

These broad measures of population, employment, and wages all tell a consistent story. For the past quarter century the Milwaukee Area has grown increasingly decentralized. Washington and Ozaukee have expanded their population, but the major growth has occurred in Waukesha county.

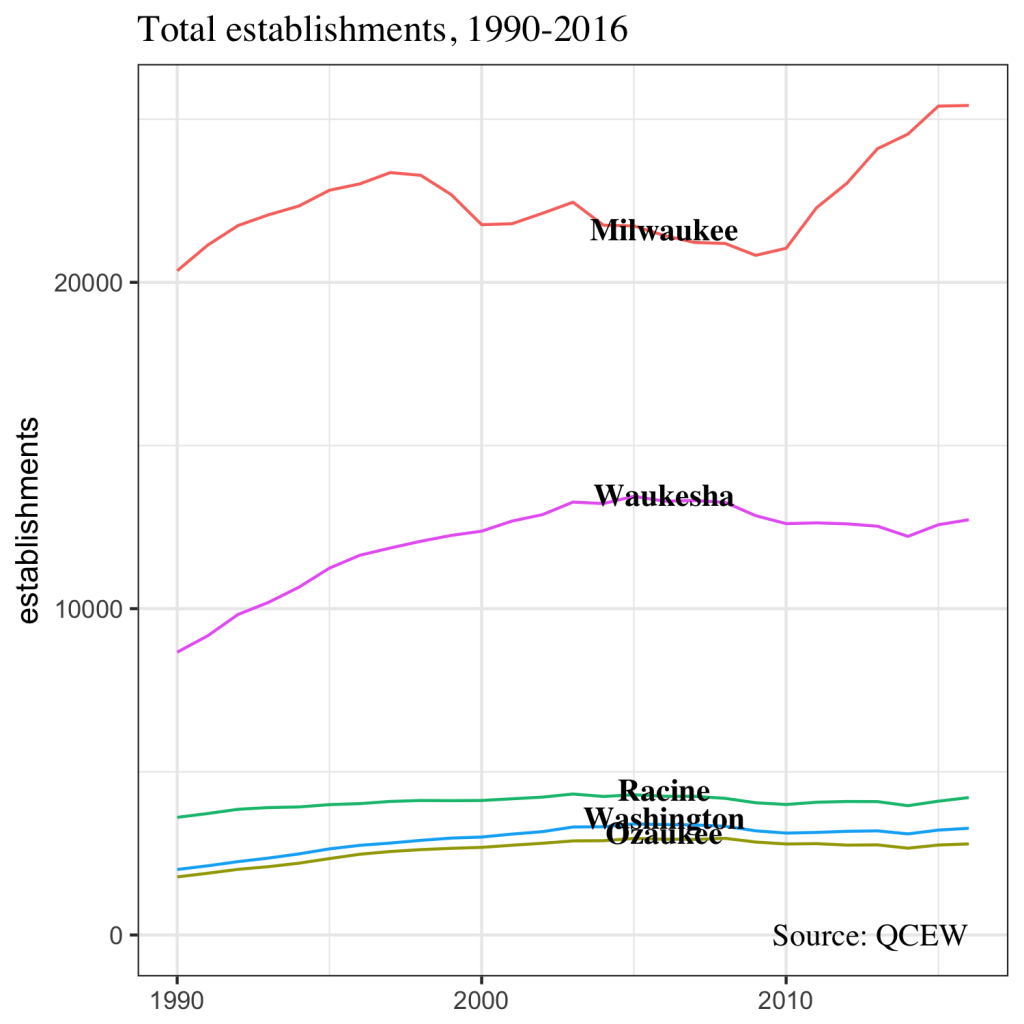

Still, several signs suggest that Milwaukee has turned the corner on some of its long-running economic struggles. The steep population loss of the 1990s has subsided, and Milwaukee City’s population now seems to be holding steady at just below 600,000. In comparison to the early and mid-2000s, the region’s recovery from the Great Recession has been fairly equal across Milwaukee and Waukesha counties. Some of the strongest evidence for Milwaukee’s ongoing revival is in the graph below. According to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Milwaukee county added 4,377 establishments in net terms from 2010 to 2016. During the same time period, the remaining four counties combined for just 481 additional establishments.[1] Milwaukee county alone still holds over half the region’s people, employs over half the region’s workers, and generates over half the region’s wealth.

[1] The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines an establishment as follows. “An establishment is commonly understood as a single economic unit, such as a farm, a mine, a factory, or a store, that produces goods or services. Establishments are typically at one physical location and engaged in one, or predominantly one, type of economic activity for which a single industrial classification may be applied. A firm, or a company, is a business and may consist of one or more establishments, where each establishment may participate in different predominant economic activity.”