The Use and Misuse of History

In his novel 1984, George Orwell imagined a future world where a government at war could switch allegiances with the country’s enemies and allies and a docile public would accept the revised version of history unquestioningly. Orwell, a keen observer of the modern world, recognized that history itself could be manufactured and manipulated in the service of broader purposes.

In his novel 1984, George Orwell imagined a future world where a government at war could switch allegiances with the country’s enemies and allies and a docile public would accept the revised version of history unquestioningly. Orwell, a keen observer of the modern world, recognized that history itself could be manufactured and manipulated in the service of broader purposes.

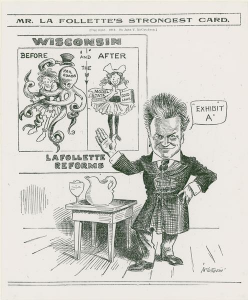

This morning’s edition of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel contains an opinion piece by Chrisitian Schneider of the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute (WPRI) entitled “Not What They Meant Democracy to Look Like.” In it, Mr. Schneider argues that the current effort to recall Governor Scott Walker and other elected state officials runs contrary to the original intent of Senator Bob La Follette and other advocates of the recall provisions of the Wisconsin State Constitution. His op ed is excerpted from a larger piece that Mr. Schneider has authored for WPRI entitled “The History of the Recall in Wisconsin.”

In the newspaper piece, Mr. Schneider makes the assertion that “a review of documents and press accounts from the time the recall constitutional amendment passed shows that the current use of the recall is far different from what the original drafters had envisioned.” His argument is that the recall provisions of the Wisconsin Constitution were intended to apply solely to judges and state senators, and not to executive branch officials such as the governor, because the two year term of office in place for governors at the time that the amendment passed would have made the recall of a governor impractical.

The historical record is completely contrary to Mr. Schneider’s assertion. Moreover, the evidence that he relies upon is completely inadequate to establish the existence of the skewed original intent that he advances.