In an earlier posting, Rick Esenberg expressed his opposition to recent George Soros-sponsored efforts to devise a plan to circumvent the operation of the Constitution’s venerable Electoral College.

In an earlier posting, Rick Esenberg expressed his opposition to recent George Soros-sponsored efforts to devise a plan to circumvent the operation of the Constitution’s venerable Electoral College.

The “problems” with the Electoral College are well-known. Its “winner-take-all” feature supposedly distorts the electoral process, and on four occasions (1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000), it has chosen a president who received fewer popular votes than one of his opponents.

Debates over the future of the Electoral College often assume that there are only two options: scrap the institution altogether or else accept that it will continue to operate as it has in the past. Scraping the Electoral College is usually assumed to require a constitutional amendment, although the Soros plan would actually leave the Constitution unchanged but seek to bind electors to cast their votes for the candidate with the largest national popular vote regardless of the results in their particular state.

There is an alternative, however, that would make the results of the Electoral College more democratic but would leave the Constitution unchanged.

Although it has long been the practice that individual states award their entire electoral vote allotment to the candidate receiving the largest number of popular votes in the state, there is no constitutional requirement that states follow this approach. In the first part of the 19th century, many states split their electoral votes, and today two states, Maine and Nebraska, have abandoned the “winner take all” rule. (In 2008, Nebraska split its electoral votes between McCain and Obama.)

In the first third of the 19th century the selection by a single state of electors supporting different candidates was a frequent feature of American presidential elections. As late as 1824, five of 24 states did just that. In 1828, three states did so, including New York, which cast 20 votes for Andrew Jackson and 16 for the incumbent John Quincy Adams. By the mid-1830’s, every state appears to have embraced the winner take all system, although in 1860, New Jersey reverted to the older system and ended up dividing its seven electors between the Republican Abraham Lincoln (4) and the Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas (3)

Article II of the United States Constitution makes it clear that each state has the power to adopt a different system of choosing electors, should it choose to do so. There are at least three ways that states could chose to apportion their electors that would produce more equitable allocations of electoral votes.

A state could simply apportion its electors on the basis of the popular vote. For example, in 2008, Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes could have divided six for Obama and four for McCain based upon Obama’s 56% to 44% margin of victory. On the other hand, such a system can run into problem because of the presence of “third” parties. Like Wisconsin, Minnesota currently has 10 electoral votes. In 2008, Obama and McCain received 54% and 44% of the popular vote, respectively, with 2% going to third parties. The Constitution requires the appointment of actual electors, so it is not obvious as to whom the tenth Minnesota elector would be assigned.

A second possibility would be for a state legislature to divide the state into “electoral districts” with each district choosing one elector. Because each state has two more electors than it has representatives in Congress, congressional districts could not be used for this purpose. Instead, states would have to create special districts. Wisconsin, for example, would have to be divided into ten districts whose sole function would be the selection of presidential electors. Obviously, this could be done, but the process would involve many of the same difficulties that arise when the state has to redraw the lines of congressional districts.

The third possibility is the approach currently taken in Maine and Nebraska. The presidential candidate receiving the largest number of popular votes in each congressional district receives one elector, and the winner of the statewide popular vote is awarded an additional two electors. In Wisconsin in 2008, Obama received the largest number of popular votes in seven of the state’s eight Congressional Districts. Consequently, under the Maine/Nebraska system he would have received nine of the state’s ten electoral votes with the other vote going to McCain.

While this approach would have had only a slightly different effect in Wisconsin (where Obama received all ten electoral votes), there are other states where the impact would have been greater. In Ohio, for example, this system would have divided the state’s twenty electoral votes evenly between Obama and McCain instead of having all twenty go to Obama. Even in large states won easily by one candidate or the other, the losing candidate would have collected electoral votes. Under this system, McCain would have received eleven electoral votes in California and four in New York, while Obama would have received eleven votes in Texas and five in Georgia.

Obviously, the great advantage of this system is that it does not require the creation of additional electoral districts. It would also create an incentive for candidates to campaign in states even if they perceived that they had no real chance of winning the overall popular vote in that jurisdiction. On the other hand, it is also possible that this system might make third party candidacies more popular since it would not be necessary to carry entire states to have a presence in the Electoral College.

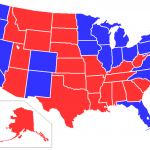

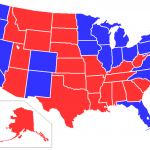

Had the Maine/Nebraska system been in effect in every state in 2008, the final result would have been a 301-237 victory for Barack Obama, compared to the actual margin of 365-173. Very few states under this system would have awarded all of their electoral votes to a single candidate. In fact, if we remove the eight jurisdictions with three electoral votes (where a divided vote was impossible), 32 of 43 jurisdictions would have divided their electoral votes. Of the eleven that would have voted unanimously, only four had more than five electoral votes, and only one (Massachusetts) had more than ten.

Although the allocation of electoral votes would have looked much different, the Maine/Nebraska system would not have produced a different result in any of the last three presidential elections (which are the only ones for which I have recalculated the vote). Obama would have won in 2008, although not by as large a margin. Earlier in the decade, the geographic dispersion of his supporters would have meant that George W. Bush would have twice been elected president under the district system. In fact, he would have won by even larger margins under this system than he did in 2000 and 2004, even though he received fewer popular votes than Al Gore in 2000. Under the Maine/Nebraska system, Bush would have defeated Gore in 2000 by a margin of 288-250 (rather than 271-266), and John Kerry in 2004 by 317-221 (instead of 286-252).

Even though the Maine/Nebraska system would not eliminate the possibility of a “minority” president, it would “decentralize” the electoral process and would better protect the rights of those who reside in less populous parts of the country to participate in the presidential election process in a meaningful way.

The challenge of course is to convince the other 48 states that it would be in their and the nation’s best interest to adopt the Maine/ Nebraska approach. Unless all states adopted the “district” approach, states retaining the winner-take-all system might actually become even more important. As critics of this approach have pointed out in the past, the original system of district elections disappeared in the early 19th century because of a perception that the winner-take-all states were able to exercise greater influence.

Of course, states could be required to adopt a district system, but that would require a constitutional amendment.

What follows is a state by state breakdown of electoral votes for the 2008 presidential election, had the Maine/Nebraska system been in effect in each state. The numbers following the name of each state are the electoral votes for Obama and McCain, respectively. In states marked with an * Barack Obama was the recipient of the largest number of popular votes.

2008 Results, Alternative Approach to Choosing Electors.

Alabama 1-8

Alaska 0-3

Arizona 2-8

Arkansas 0-6

*California 44-11

*Colorado 5-4

*Connecticut 7-0

*Delaware 3-0

*Florida 12-15

Georgia 5-10

*Hawaii 4-0

Idaho 0-4

*Illinois 18-3

*Indiana 5-6

*Iowa 6-1

Kansas 1-5

Kentucky 1-7

Louisiana 1-8

*Maine 4-0

*Maryland 8-2

*Massachusetts 12-0

*Michigan 14-3

*Minnesota 7-3

Mississippi 1-5

Missouri 3-8

Montana 0-3

Nebraska 1-4

*Nevada 4-1

*New Hampshire 4-0

*New Jersey 12-3

*New Mexico 4-1

*New York 27-4

*North Carolina 8-7

North Dakota 0-3

*Ohio 10-10

Oklahoma 0-7

*Oregon 6-1

*Pennsylvania.. 11-10

*Rhode Island 4-0

South Carolina 1-7

South Dakota 0-3

Tennessee 2-9

Texas 11-23

Utah 0-5

*Vermont 3-0

*Virginia 8-5

*Washington 9-2

West Virginia 0-5

*Wisconsin 9-1

Wyoming 0-3

District of Columbia 3-0

Presumably the DC election would be on a winner-take-all basis, as it is in other states with three electoral votes.

The Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. FEC strikes down as unconstitutional a federal law that prohibits corporations and unions from using general treasury funds to make independent expenditures that expressly advocate the election or defeat of candidates for office. The majority opinion, written by Justice Kennedy, ignores hundreds of years of Supreme Court history in interpreting the subjects of federalism, free markets, and free speech. In its place, Justice Kennedy presents a textualist interpretation of the First Amendment that is divorced from any history or context. Justice Kennedy engages in the sort of “faux originalism” (syn. “fake,” “artificial,” “false”) that has been criticized by Judge Richard Posner. Kennedy places a historical glaze on his own personal values and policy preferences, and calls the result the “original understanding” of the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. FEC strikes down as unconstitutional a federal law that prohibits corporations and unions from using general treasury funds to make independent expenditures that expressly advocate the election or defeat of candidates for office. The majority opinion, written by Justice Kennedy, ignores hundreds of years of Supreme Court history in interpreting the subjects of federalism, free markets, and free speech. In its place, Justice Kennedy presents a textualist interpretation of the First Amendment that is divorced from any history or context. Justice Kennedy engages in the sort of “faux originalism” (syn. “fake,” “artificial,” “false”) that has been criticized by Judge Richard Posner. Kennedy places a historical glaze on his own personal values and policy preferences, and calls the result the “original understanding” of the First Amendment.

As we head into the fall election cycle, one of the most important consequences of state legislative and gubernatorial races will be the impact on redistricting in 2011.

As we head into the fall election cycle, one of the most important consequences of state legislative and gubernatorial races will be the impact on redistricting in 2011.