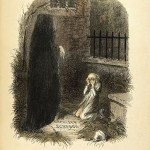

A Visit From the Ghost of Jury Service Past

What do you remember about November 29, 1995? That was the day when one of the jurors in Jesse Webster’s drug trafficking trial was out sick. The next day, with all twelve jurors again present, Webster was convicted. Many years later, Webster claimed in a petition for post-conviction relief that the eleven jurors who showed up on November 29 improperly proceeded with deliberations that day at the direction of a rogue bailiff.

What do you remember about November 29, 1995? That was the day when one of the jurors in Jesse Webster’s drug trafficking trial was out sick. The next day, with all twelve jurors again present, Webster was convicted. Many years later, Webster claimed in a petition for post-conviction relief that the eleven jurors who showed up on November 29 improperly proceeded with deliberations that day at the direction of a rogue bailiff.

In response to the petition, an investigator tracked down the jurors to ask them what they recalled about November 29, 1995. The interviews took place between 2001 and 2006. (Evidently, the investigation was not exactly a high priority.) The results, as the Seventh Circuit put it with considerable understatement in an opinion last week, were a “mixed bag”:

The first question was: “The court records show that on one day one of the jurors did not appear. Do you recall any such time when that might have occurred?” Seven jurors said they did not recall a juror being absent; four jurors said they did. Of the four who did remember a juror’s absence, three recalled that an alternate juror replaced the absent juror, a claim wholly unsubstantiated by court records. One of the four thought the juror was absent on the day before Thanksgiving; another claimed the juror was absent on the first two days of deliberations. Two correctly recalled that the absent juror was male; one said the absent juror was female. The second question was: “Do you recall being sent home early because of this juror’s absence?” The jurors answered either “no” or that they did not recall.