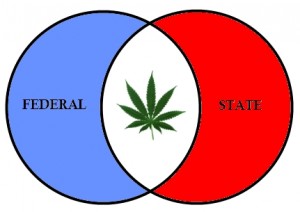

Does Federal Law Actually Preempt Relaxed State Marijuana Laws?

The Cato Institute’s Ilya Shapiro recently spoke at the Law School concerning the status of relaxed state marijuana laws in light of the federal Controlled Substances Act’s continued prohibition of activities that these state laws now allow. This is a timely question with, it turns out, a less-than-certain answer. More precisely, it demands an answer that is more nuanced, and less categorical, than one might initially be inclined to give.

The Cato Institute’s Ilya Shapiro recently spoke at the Law School concerning the status of relaxed state marijuana laws in light of the federal Controlled Substances Act’s continued prohibition of activities that these state laws now allow. This is a timely question with, it turns out, a less-than-certain answer. More precisely, it demands an answer that is more nuanced, and less categorical, than one might initially be inclined to give.

One’s initial answer is likely that these state laws are preempted—that is, rendered void and unenforceable—because of the federal statute. It is conventional constitutional doctrine, after all, that the U.S. Constitution’s Supremacy Clause makes valid federal law supreme over conflicting state law. Moreover, because the U.S. Supreme Court in Gonzales v. Raich (2005) deemed the federal marijuana prohibition to be a valid exercise of Congress’ commerce power, the specific question of whether state marijuana laws are vulnerable to preemption seems already to have been answered.

Mr. Shapiro makes an important observation, however.