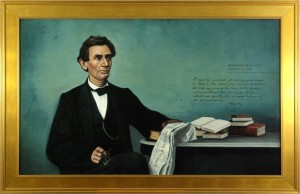

The Emancipation Proclamation—Sesquicentennial Reflections

January 1, 2013, marks the 150th anniversary of President Lincoln’s final Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the freedom of slaves in rebellious states. The decree was controversial in Lincoln’s time and seems often to be misunderstood in ours. The objective of this blog post, accordingly, is to survey the context, chronology, and consequences of the Proclamation as we observe the sesquicentennial of its issuance.

January 1, 2013, marks the 150th anniversary of President Lincoln’s final Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the freedom of slaves in rebellious states. The decree was controversial in Lincoln’s time and seems often to be misunderstood in ours. The objective of this blog post, accordingly, is to survey the context, chronology, and consequences of the Proclamation as we observe the sesquicentennial of its issuance.

The Context—Summer 1861 through Fall 1862

Through the latter half of 1861 and well into 1862, it was not at all self-evident that the Union would win the Civil War. Particularly in the east, the most symbolic military theater, the Confederate Army secured numerous victories or military stalemates, the latter of which were essentially as advantageous for it as the former. Despite having superior financial and industrial resources, the Union Army’s deficit of aggressive battlefield leadership, lack of well-trained or seasoned troops, and comparative unfamiliarity with the terrain repeatedly hampered Union military actions.

Lincoln was painfully cognizant of these problems, especially the operational timidity of his top brass, purportedly remarking at one point that if General George B. McClellan was not going to use the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln “would like to borrow it, provided he could see how it could be made to do something.” President Lincoln also knew that popular support for the war, as casualties mounted and the prospect of national conscription loomed, could not long endure without visible Union success in the east. At the same time, the President was aware that the Confederacy was seeking the recognition and material support of European nations such as England and France, and that every Confederate victory appeared to make this objective more attainable.

It was this array of circumstances, among others, that prompted President Lincoln to take the manifestly drastic step of issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. Only against this political and military backdrop, in fact, can the Proclamation and its timing be fully comprehended. In order to explain why this is so, it is necessary to walk through the events leading up to the Proclamation and then to examine the substance and scope of the Proclamation itself.