In her majority opinion in the landmark civil rights case Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 342-44 (2003), Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote:

In her majority opinion in the landmark civil rights case Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 342-44 (2003), Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote:

Enshrining a permanent justification for racial preferences would offend this fundamental equal protection principle. We see no reason to exempt race-conscious admissions programs from the requirement that all governmental use of race must have a logical end point. . . . From today’s vantage point, one may hope, but not firmly forecast, that over the next generation’s span, progress toward nondiscrimination and genuinely equal opportunity will make it safe to sunset affirmative action.

Although O’Connor and her colleagues upheld the constitutionality of the University of Michigan Law School’s affirmative action program at issue in Grutter, her opinion reflected a belief that affirmative action programs would draw to a close at some future point.

Data released by the College Board, the organization that administers the SAT exam, at the end of August suggests, however, that the end date for affirmative action is probably still a long way off.

Once again, Non-Hispanic whites and Asians scored significantly higher on the SAT than African-Americans and Hispanics, and the pattern of scores provides no evidence that the gap is closing. Over 1.5 million college-bound seniors took the test, the largest number in history.

The SAT now consists of three sections — writing, critical reading, and mathematics — each of which is scored on a scale that ranges from 200 to 800. Since April 1995, the targeted median score on each test has been 500 (rather than 450 as it was before). Consequently, the range of combined scores is 600 to 2400, with an “average” score being 1500. The actual average for the 2008-09 academic year was 1504, essentially the same as it was the previous year.

For the test as a whole, Asian students scored 1633 compared to 1581 for non-Hispanic whites, with most of the disparity resulting from a significantly higher mathematics score. Other groups did not do nearly as well. The scores of Native Americans and Eskimos averaged 1448; Hispanics, 1364; and African-Americans, only 1273. Males of all races, who counted for only 46.5 percent of test takers, outscored females, 1523 to 1496.

Much of the discrepancy in racial performance is due to socio-economic factors that adversely affect black and Hispanic adolescents. Low family incomes, single-parent homes, low levels of education in the family, and the lack of role models who have achieved academic success all contribute to poor test performance. For example, students of all races with family incomes of $200,000 or more averaged 1702 on the SAT; those with family incomes of below $20,000 scored 1321. Students whose parents had at least one graduate degree averaged 1683; those who parents had not finished high school scored only 1281.

With this kind of disparity in SAT scores, only affirmative action programs can guarantee that African-Americans and Hispanics will be proportionally represented at America’s more selective colleges and universities. Although we may reach Justice O’Connor’s sunset at some point, right now we are clearly still in the middle of the day.

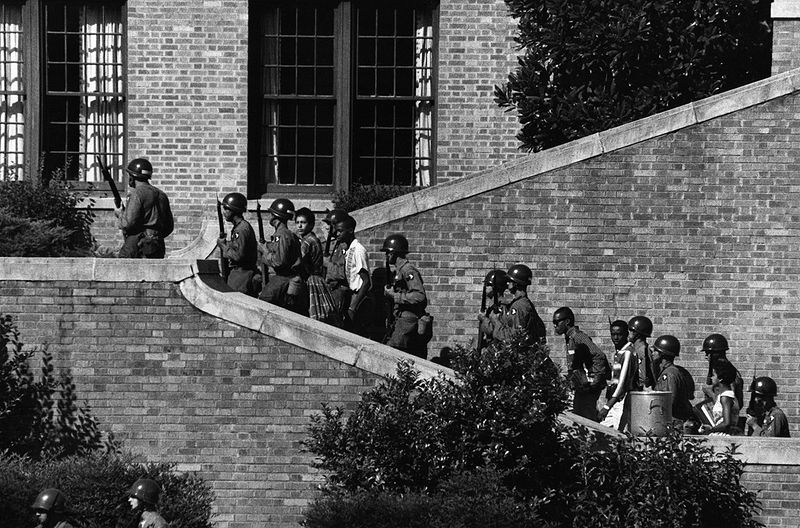

“That crucible moment” – that’s a phrase Ernest Green used to describe the period when he and eight other African American students enrolled in and attended Little Rock Center High School in 1957. It took the president of the United States and 10,000 soldiers to help them get in the door in deeply segregationist Arkansas. But more than anything, their success took the determination and self-control that the nine showed against almost overwhelming opposition and hate. The events of that fall became a huge landmark in the fight to end official segregation.

“That crucible moment” – that’s a phrase Ernest Green used to describe the period when he and eight other African American students enrolled in and attended Little Rock Center High School in 1957. It took the president of the United States and 10,000 soldiers to help them get in the door in deeply segregationist Arkansas. But more than anything, their success took the determination and self-control that the nine showed against almost overwhelming opposition and hate. The events of that fall became a huge landmark in the fight to end official segregation.

In her majority opinion in the landmark civil rights case Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 342-44 (2003), Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote:

In her majority opinion in the landmark civil rights case Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 342-44 (2003), Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote: