Professor Greipp’s fascinating post on Lois Kuenzli Collins, an early female graduate of Marquette Law School, made reference to Ms. Collins’ law degree being upgraded to a J.D. in the late 1960s. That was actually a fairly common occurrence at that time, as thousands of American lawyers in the 1960s found themselves the possessors of a newly styled doctoral law degree. Between 1964 and 1969, at the encouraging of the American Bar Association, most American law schools (including Marquette) upgraded their basic law degree from the traditional “LL.B.” to “J.D.,” to reflect the by then almost universal postgraduate status of the degree. For good measure, most also made the change retroactive, subject to the graduate returning his or her old degree for a new one.

Professor Greipp’s fascinating post on Lois Kuenzli Collins, an early female graduate of Marquette Law School, made reference to Ms. Collins’ law degree being upgraded to a J.D. in the late 1960s. That was actually a fairly common occurrence at that time, as thousands of American lawyers in the 1960s found themselves the possessors of a newly styled doctoral law degree. Between 1964 and 1969, at the encouraging of the American Bar Association, most American law schools (including Marquette) upgraded their basic law degree from the traditional “LL.B.” to “J.D.,” to reflect the by then almost universal postgraduate status of the degree. For good measure, most also made the change retroactive, subject to the graduate returning his or her old degree for a new one.

An American Bar Association committee had recommended that the law degree be called the juris doctor as early as 1906, and a small number of law schools, most notably the University of Chicago, had long called the basic law degree the J.D. However, until the late 1960s the vast majority of schools used the designation of LL.B. or B.L. which suggested that the law degree was an undergraduate degree (as it still is in most places in the world).

What is much less well known is that in an earlier era, some law schools simultaneously offered both the LL.B. and J.D. degrees. While the original law degree awarded by Marquette was the LL.B., between 1926 and 1943, Marquette offered its students the option of earning either an LL.B. degree or a J.D. degree. This innovation apparently originated with Dean Max Schoetz, but was continued after his untimely death in 1927.

Both of the two law degrees were normally earned in three years. However, to earn the J.D., a student had to (1) have already earned an undergraduate degree in a field other than law–admission to Marquette required only two years of college between 1926 and 1934 and only three after that year—(2) compile an average grade of 88 (out of 100) in all law courses (compared to 77 for LL.B. candidates); and (3) prepare an acceptable thesis on a law-related topic in his (or her) third year. (The student was also required to assign the copyright in the thesis to the law school dean.)

There was no formal advantage to the J.D. degree, at least in regard to bar admission. One did not need to have a law degree of any sort to take the Wisconsin bar examination until 1940—three years of study in or outside of a law school was all that was required. Moreover, after 1933, either degree qualified its holder for automatic admission to the Wisconsin bar under the diploma privilege, which was extended to Marquette that year. The University of Wisconsin, which had had the diploma privilege since 1870, had never awarded a J.D. degree, so there was no basis on which to distinguish between the two degrees. There was also no evidence that law firms placed any special premium on hiring graduates with the J.D. degree.

Given this lack of immediate advantage, few Marquette students appear to have even attempted the J.D. degree. In any given year, only a handful of students met the full set of qualifications, and less than 40 such degrees were awarded in the decade and a half that the option existed. The last of the original J.D.’s at Marquette were awarded in 1939, although the option remained on the books until 1943 (or perhaps a year or two longer as records for the law school for 1944 and 1945 are almost non-existent).

Our colleague Jim Ghiardi, who attended Marquette Law School from 1939 to 1942, recalls that the J.D. degree fell out of favor as students began to realize that the extra work necessary to earn the degree provided them with no real additional benefit, particularly during a Great Depression with a world war looming on the horizon.

Lois Kuenzli Collins was enrolled at the law school when the J.D. option was created, and like most of her classmates she did not qualify for the “higher” degree. However, her recollection of the distinction between the two degrees probably explains her excitement forty years later when her degree was “upgraded” from an LL.B. to a J.D.

As it turns out, there was nothing unique about Marquette’s awarding both J.D. and LL.B. degrees in the 1920s and 1930s. The practice was particularly widespread, it appears, in the Midwest.

As late as 1961, there were still 15 ABA-accredited law schools in the United States which awarded both LL.B. and J.D. degrees. The fifteen included George Washington University, Chicago-Kent, DePaul, John Marshall, Loyola of Chicago, Northwestern, Indiana, Drake, Iowa, Washburn, Michigan, Detroit College of Law, Wayne State, Ohio State, and Willamette. At least by a broad definition, all of the 15 were located in the Midwest except for George Washington (D.C.) and Willamette (Ore.).

In all of the listed schools except Northwestern and Iowa, the largest number of graduates received the LL.B. degree. (At Northwestern and Iowa, the J.D. degree was the more commonly awarded.) The practice was not exactly dying out either, as the following year both the University of North Dakota and the University of Oregon joined the list of schools awarding both degrees. Duke adopted the J.D./LL.B. distinction after 1961, and the two options were listed in the Duke Law School catalog as late as 2007, although the school apparently had not awarded an LL.B. degree since the 1960s.

As the number of law students who entered law schools with college degrees increased in the 1950s and 1960s, a number of institutions apparently used the J.D./LL.B. distinction to encourage would-be law students to complete their undergraduate degrees before beginning their legal studies. (If they failed to do so, they got the bachelor’s degree, not the doctorate.)

Presumably, the practice of awarding two different degrees was originally related to the argument that it did not make sense to award a second bachelor’s degree to someone who already had one. (A previous undergraduate degree appears to have always been a prerequisite for the pre-1960s J.D.) Unfortunately, there does not appear to be an easily accessible source that identifies when individual schools began to award the two law degrees. The practice started at Marquette in 1926 and at Chicago-Kent in 1933, but it could well predate the 1920s at other schools.

The concentration of the “two types of law degree” schools in the Midwest (and particularly in Chicago) seems likely related to the presence of the highly prestigious University of Chicago which from its founding always required its students to have college degrees, and, beginning in 1902, it always awarded it graduates the J.D. degree.

In contrast, Harvard Law School, which was the first law school to insist on a prior undergraduate degree as a prerequisite for admission, considered the possibility of awarding some sort of doctorate in law in the early 1900s but decided to stay with the LL.B. Harvard also invested heavily in the early 20th century in graduate law programs that resulted in the award of LL.M. and S.J.D. degrees. Given that this graduate degree terminology did not really fit if the first law degree was called a doctorate, Harvard retained the undergraduate designation for its law degree. Given its great prestige, whatever was done at Harvard Law School was likely to imitated at law schools across the country.

It is not clear why a few schools like Marquette and the University of Washington once awarded both LL.B. and J.D. degrees but decided to stop doing so long before the 1960s. Washington eliminated the J.D. degree in 1938 and, as mentioned above, Marquette followed in the mid-1940s. The Marquette experience suggests that the decision may have been related to a lack of student interest in the more demanding degree, as well as to a general revamping of the law school that occurred immediately after World War II under the leadership of Dean Francis Swietlik.

There were a few other variations on the J.D. degree as well. At Georgetown in the 1930s, one could earn a J.D. degree, but only after earning an LL.B. degree, which made it more in the nature of an LL.M. or an S.J.D. degree. Another variation occurred at William & Mary where, for much of the 20th century, graduates received a B.C.L. degree rather than either the LL.B. or the J.D.

By the end of the 1960s, the variations in terminology had been eliminated and the letters “JD” are now synonymous with the words “law degree”. However, we live in a time when many of the assumptions of contemporary legal education are being reexamined, and the legitimacy of much of what has been long taken for granted is being reconsidered.

Perhaps one result of the current anxiety will be a movement away from the one-size-fits-all J.D. degree of the late 1960s to something more akin to the multiple-degree model embraced by Marquette in the 1920s and 1930s.

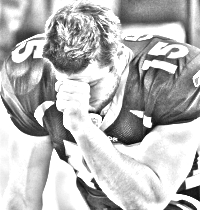

Much has been made of Broncos quarterback Tim Tebow’s outward expressions of his Christian faith, especially his practice of kneeling in moments of prayer—“Tebowing” as it is now called—after touchdowns, some of them admittedly a bit miraculous.

Much has been made of Broncos quarterback Tim Tebow’s outward expressions of his Christian faith, especially his practice of kneeling in moments of prayer—“Tebowing” as it is now called—after touchdowns, some of them admittedly a bit miraculous.