Money, Art and Crime

Crime often pays, and sometimes pays very well. Both the drug dealer with a pile of cash in the basement and the insider trader with a huge portfolio in an off-shore account face a common problem: How to use the cash without being targeted by law enforcement or tax collectors. The solution is “money laundering,” a banal phrase that accurately conveys how illegitimate wealth is cleaned and pressed to appear lawful – and hence useable.

Crime often pays, and sometimes pays very well. Both the drug dealer with a pile of cash in the basement and the insider trader with a huge portfolio in an off-shore account face a common problem: How to use the cash without being targeted by law enforcement or tax collectors. The solution is “money laundering,” a banal phrase that accurately conveys how illegitimate wealth is cleaned and pressed to appear lawful – and hence useable.

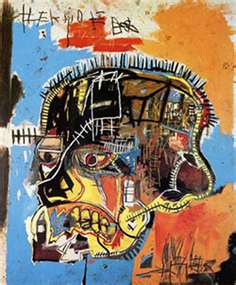

On September 5, 2012 the Law School hosted a packed lecture, “Money Laundering Perfected by Art,” presented by the Hon. Fausto Martin De Sanctis, a leading federal judge from Brazil, and Karine Moreno-Taxman, an assistant United States Attorney in the Eastern District of Wisconsin. Currently a fellow at the Federal Judicial Center in Washington D.C., Judge De Sanctis has been in the forefront of Brazil’s efforts to crackdown on international and domestic money laundering. Judge De Sanctis described the myriad forms that money laundering can assume, especially through the use of museum-quality art. Paintings and sculptures, for example, leave no money trails. Art dealers jealously guard the confidentiality of their patrons, which only facilitates stealth transactions. Judge De Sanctis talked about the legal battles involving Jean Michel Basquiat’s “Hannibal” (see image), an $8 million painting smuggled from Brazil to the U.S. by persons implicated in the Banco Santos financial scandal (Brazil’s answer to Bernie Madoff).

Attorney Moreno-Taxman, who translated for Judge De Sanctis, also talked about gaps in domestic (U.S.) and international law which make these crimes hard to detect and complicate the recovery of tainted art, like “Hannibal.” An interesting subtheme was Brazil’s efforts to implement the rule of law since 1988, when it abandoned its military dictatorship and adopted a written constitution.