House Retirements and Targeted Districts

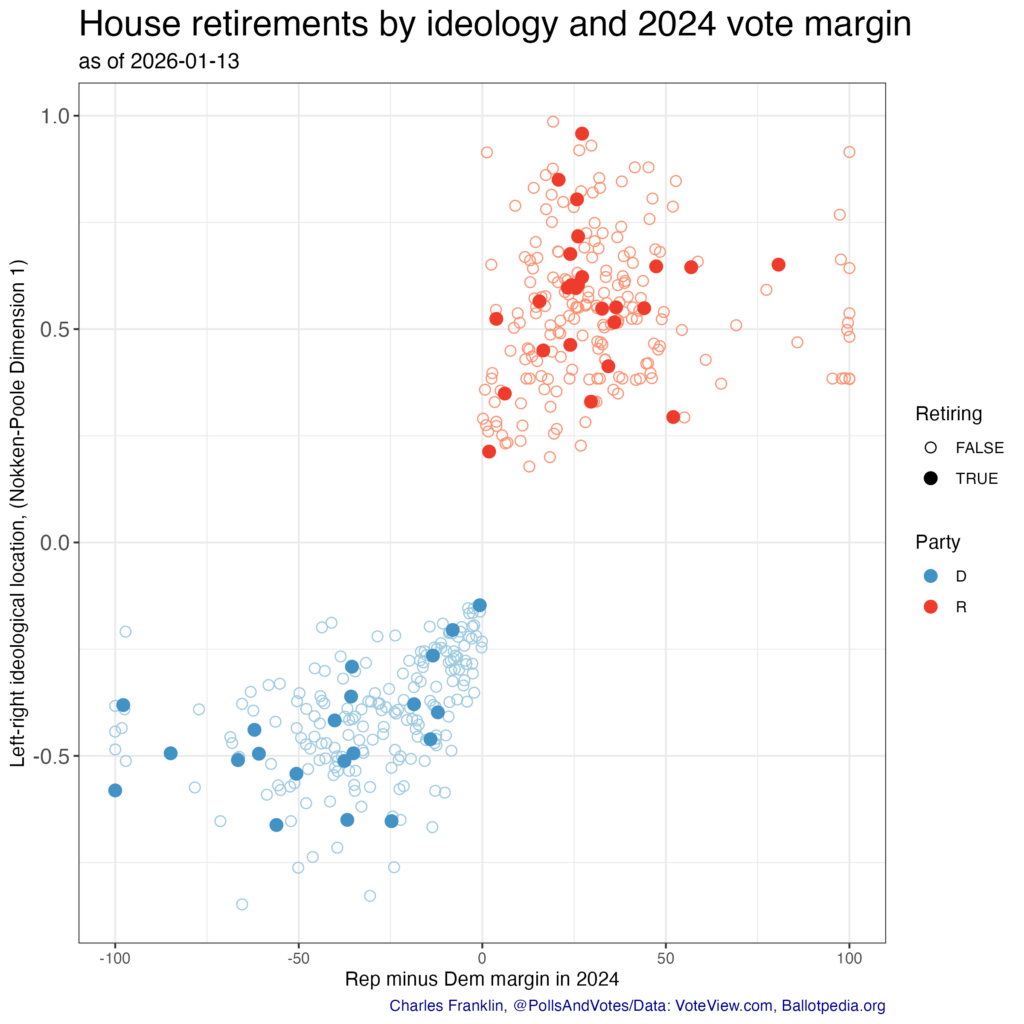

While a substantial number of members of the House of Representatives are retiring, don’t expect these retirements to produce many flipped seats or shifts in the ideological makeup of either party.

As of January 13, 47 members of the House have announced their retirement, 21 Democrats and 26 Republicans. (I’m not counting resignations by Majorie Taylor Greene and Mikie Sherrill whose seats will be filled with special elections this year.)

The retirement rate has been running a bit ahead of recent cycles as of this date, which were 42, 34, 41, and 40 from 2018 to 2024. Still, I don’t think we are seeing extraordinarily high levels of retirements, as some commentary suggests. In the end those previous four cycles produced totals of 52, 36, 49 and 45 retirements, suggesting we may end up in the mid-to-upper 50s this year. Past retirements are from Ballotpedia.org.

The main point I want to make here is that the retirements are spread pretty widely throughout both Republican and Democratic caucuses by ideology and 2024 vote margin. The solid dots are retiring members. These are not endangered incumbents who barely scraped by in 2024, nor are they ideological outliers relative to their caucuses.

The figure shows all House members by vote margin and by left-right ideology, using Nokken-Poole dimension 1 ideology scores from VoteView.com. These scores are based on roll call votes by the members. Nokken-Poole is a variant of the widely used Nominate scores. Nokken-Poole scores range from -0.848 for the most liberal member to 0.986 for the most conservative member. Vote margin is the percentage for the Republican candidate minus the percentage for the Democrat, so negative margins are Democratic wins and positive ones are Republican victories.

Among Republicans, the median 2024 vote margin is 28.2 percentage points, and the median for retiring Republicans is 26.1 points. On ideology, the median Nokken-Poole score is 0.542 (higher scores are more conservative.) Among retiring Republicans the median is 0.581

Democratic retirees have somewhat larger vote margins, -36.8 percentage points, than their caucus as a whole, -27.0 points. On ideology, the retiring Democrats are also more liberal, -0.461, than the full Democratic caucus, -0.394. These are modest differences, however, and the figure makes clear retirements are well scattered throughout both caucuses.

The upshot of this distribution of retirements is that it does not open up many opportunities for turnover as most retirees enjoyed reasonably secure margins in 2024. Nor are retirements likely to significantly shift the ideological balance in the House given that retirees are ideologically pretty representative of their caucuses. While open races are less predictable than incumbent ones, the strong partisan lean of most of these districts means we should expect no more than a handful of these seats to potentially flip.

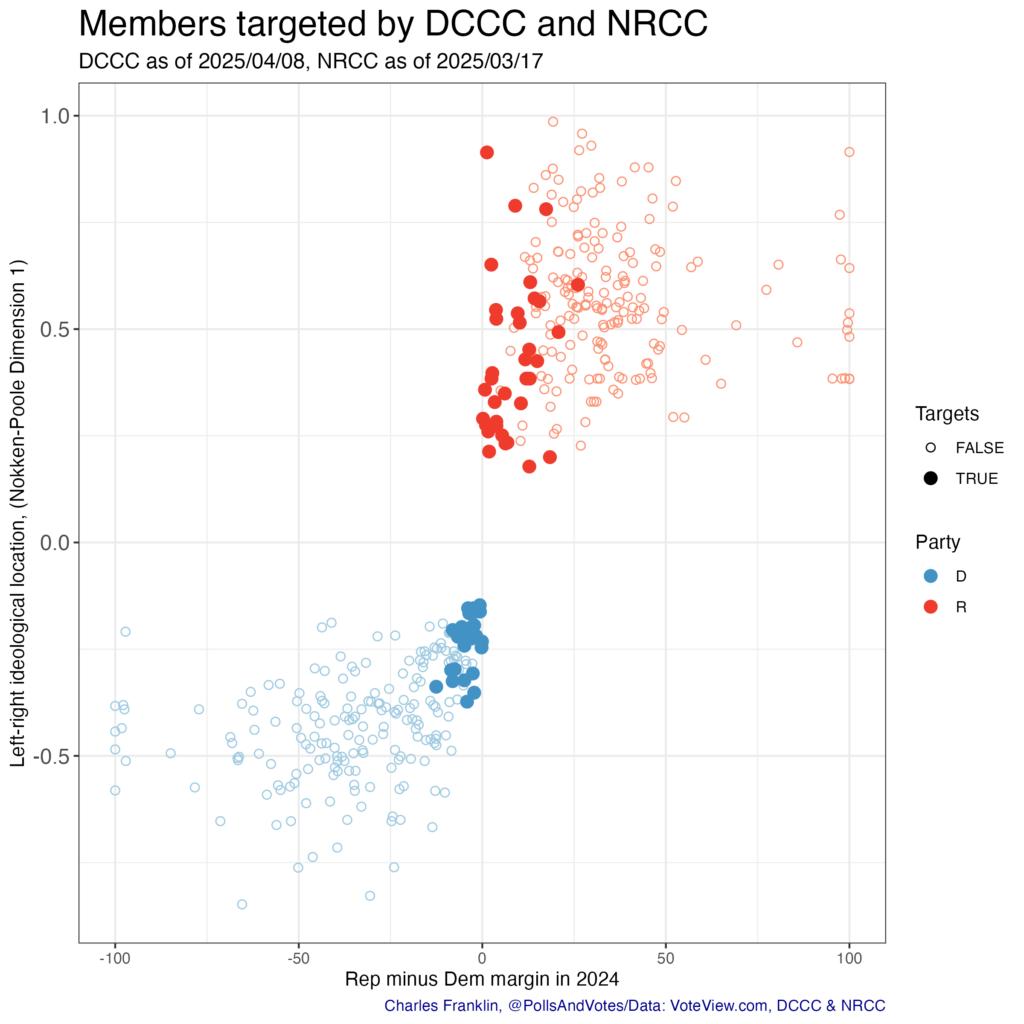

DCCC and NRCC target districts

Both the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committe (DCCC) and the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) have released lists of districts being targeted as pick up opportunities. Compare this figure with the retirements above. The targeted districts are, as you would expect, far more concentrated in races that were narrowly decided in 2024. (These lists were released by the NRCC on March 17, and by the DCCC on April 8. They do not include changes or additions after some states redistricted in 2025. These are the members’ districts in the 119th congress.)

Republicans on the DCCC list have a median vote margin of 6.8 percentage points, much closer than the caucus median of 28.2 points. They are also less conservative, 0.384, than the full caucus, 0.542.

Democrats on the NRCC list also had much closer 2024 races, with a median of -3.2 percentage points compared to -27.0 for the full caucus. These Democrats are also less liberal than the caucus, with a median Nokken-Poole score of -0.221 compared to the caucus median of -0.394.

If you are looking for change in the House, look at the districts each of the parties are focusing on. They have a much greater chance of flipping than the seats of retiring members, and would be more likely to remove relatively moderate members of either party. The latter fact will also contribute to polarization in the House. Rather than target ideologically extreme members of the opposition party, both Democats and Republicans target close races, which also happen to be where the most relatively moderate members are.