Wisconsin voters remain intensely polarized over Donald Trump

Writing this feels like the old SNL gag “Francisco Franco is still dead.” Attitudes toward Donald Trump are still polarized. Still, I think it’s worth pointing out that several months into the largest pandemic in a century, Donald Trump’s approval rating (in Wisconsin) hasn’t budged.

We’ve now conducted two polls during the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying economic shutdown in Wisconsin. Political opinion on actions taken by the state government has shifted, and Governor Tony Evers job approval has fluctuated by double digits in each poll.

But by now it is clear. Donald Trump has not benefited from a significant rally ’round the flag effect, nor has he seen any real decline in his popularity. His overall approval rating was net 0 in late February, -1 in late March, and -2 in early May. Tony Evers, by contrast, began with an approval rating of +12 in February; this jumped to +36 in late March, and fell back to +26 just a month later.

| Poll dates | Trump | Evers |

|---|---|---|

| 2/19-23/20 | 0 | 12 |

| 3/24-29/20 | -1 | 36 |

| 5/3-7/20 | -2 | 26 |

What’s remarkable isn’t just that Wisconsin voters have made up their minds about Trump. A large number of Wisconsinites hold intensely strong opinions about Trump. Wisconsin is often discussed nationally as the most divided state in the nation–the most likely “tipping point” in a national election. To an outsider this might suggest that Wisconsin is full of undecided, persuadable voters. Our data suggests otherwise. Wisconsin is just more narrowly divided between strong partisans than most other states.

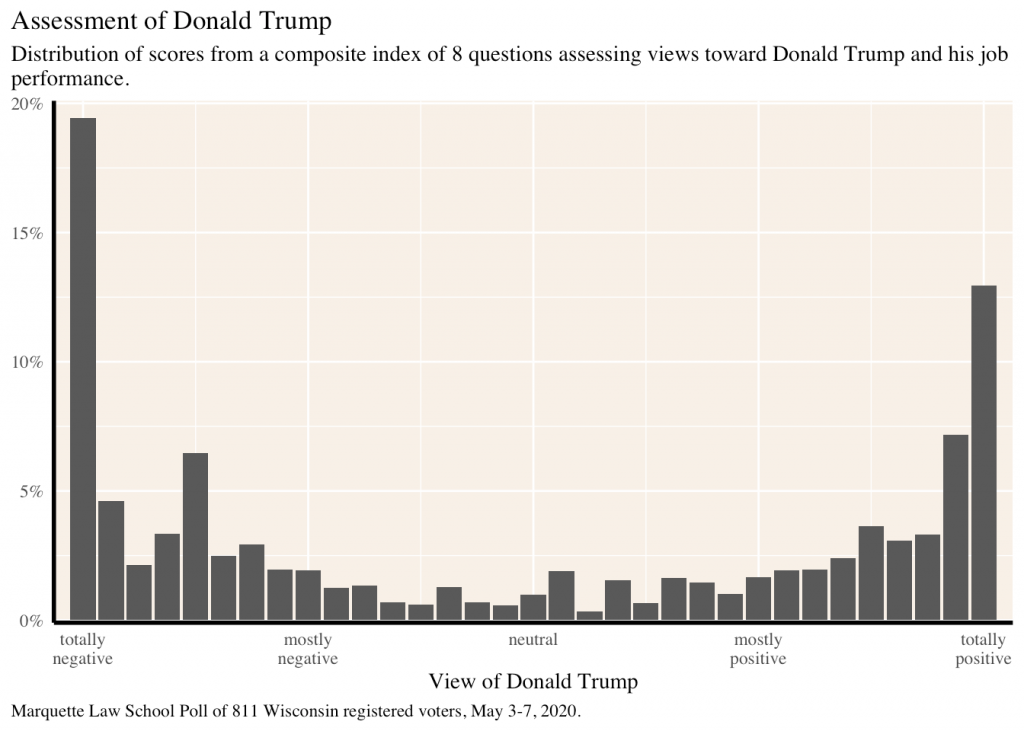

In our latest poll we asked 8 questions assessing different aspects of Donald Trump’s job performance. They covered things from Trump’s handling of immigration to his policy decisions in response to the pandemic. I combined all of these questions to create one metric for intensity of Trump support. If a respondent evaluated Trump positively I gave them a score of 1. If they evaluated Trump negatively, they received -1. “Somewhat” positive or negative evaluations received a half point in the appropriate direction. A score of 8 means the respondent answered every question in the most pro-Trump way possible, and a score of -8 means the reverse.

Here are the results. Nineteen percent of Wisconsin registered voters gave Trump the worst score they could, and 13 percent gave him a perfect 8/8. Twenty-six percent rated him -7 or worse, while 23 percent gave him a 7 or better. About half of Wisconsin voters have an overwhelmingly positive or negative opinion of the president. Just 5 percent give him a neutral score within the range 1 to -1.

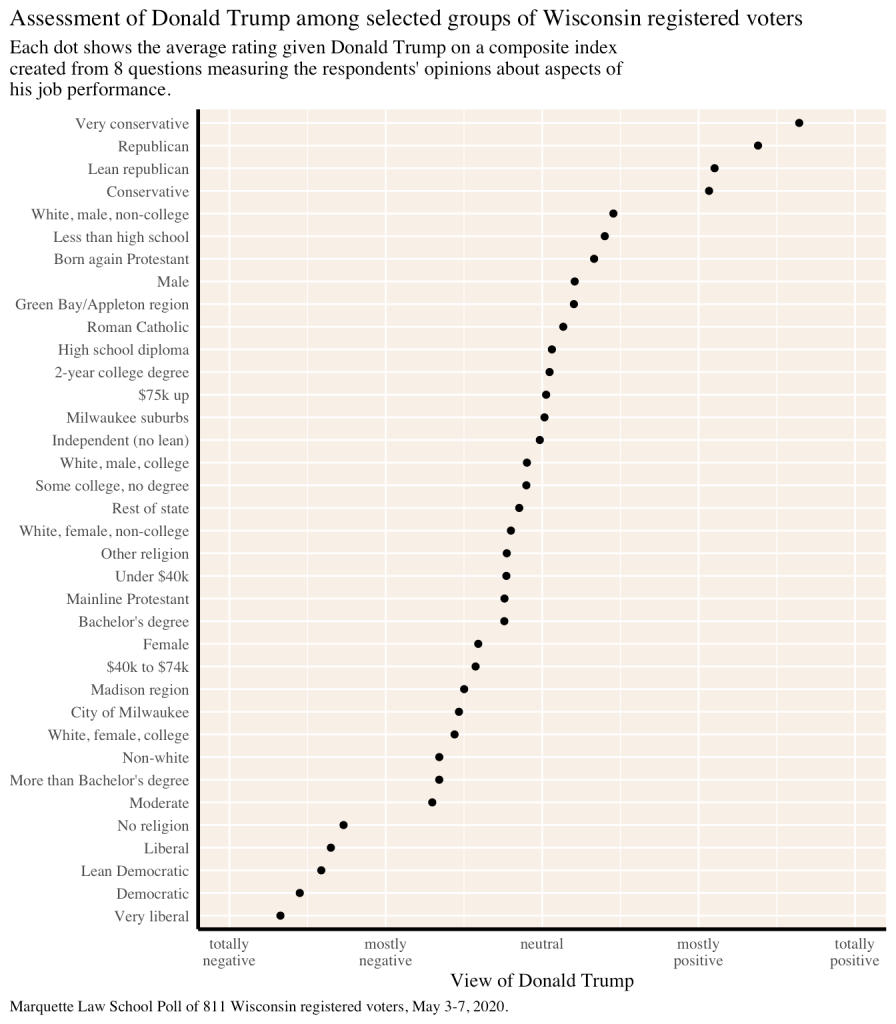

Here is the average score given Donald Trump by different demographic groups in the state of Wisconsin. As expected, party and ideological identification have the strongest polarization. The most narrowly divided group of all in this survey are residents of the Milwaukee suburbs.

Here is the average score given Donald Trump by different demographic groups in the state of Wisconsin. As expected, party and ideological identification have the strongest polarization. The most narrowly divided group of all in this survey are residents of the Milwaukee suburbs.

Most of the groups in this chart with average scores close to 0 are not, in reality, full of voters with neutral opinions on Trump. Often, they just have close to even mixes of strongly and oppositely polarized voters.

Consistent with Joe Biden’s small (and within the margin of error) lead, Trump’s average rating in this survey was -0.5. Given the potentially decisive importance of Wisconsin’s 10 electoral college votes and the state’s historically razor-thin margins of victory, I anticipate that both Democrats and Republicans will pursue aggressive turnout and persuasion strategies this fall. Even a tiny set of voters could prove pivotal.

Consistent with Joe Biden’s small (and within the margin of error) lead, Trump’s average rating in this survey was -0.5. Given the potentially decisive importance of Wisconsin’s 10 electoral college votes and the state’s historically razor-thin margins of victory, I anticipate that both Democrats and Republicans will pursue aggressive turnout and persuasion strategies this fall. Even a tiny set of voters could prove pivotal.