Formal legal education in Milwaukee is said to have begun on October 12, 1892, when eleven students gathered to study law under the tutelage of local attorneys. The group called itself the Milwaukee Law Class and secured volunteer services of its instructors, William H. Churchill, Sr., and Franklin Spies, thus avoiding the need to charge tuition. Mr. Churchill was the regular lecturer on Torts and related subjects; Mr. Spies taught Contracts. In 1896, with the addition of several other faculty members, the institution changed its name to Milwaukee Law School. All classes were held at night in various rented locations in downtown Milwaukee.

In 1908, neighboring Marquette University was looking to expand its academic offerings, having recently added the Schools of Medicine and Dentistry to the original undergraduate college. At the time, there were two law schools in the city: the more-established Milwaukee Law School and the barely two-year-old and financially strapped Milwaukee University Law School. Marquette assumed sole ownership of both schools in September 1908, naming its newly acquired unit the Marquette University College of Law. A day division was added for full-time students, and all classes initially were held in Johnston Hall, which still stands. Two years later, the College of Law moved to the adjacent Mackie Mansion, a remodeled residence at the corner of North 11th Street and Grand Avenue, the early-twentieth-century name for Wisconsin Avenue. The first dean was Hon. James G. Jenkins, a retired judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

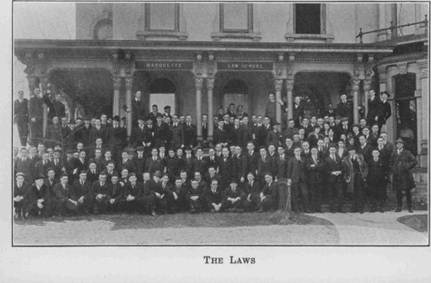

Marquette Law School community assembled in front of Mackie Mansion, ca. 1920

The 1920s marked a period of extraordinary growth and development for Marquette University Law School, as it was renamed in 1923. During the decade and a half of university affiliation, enrollment had more than doubled to 300 students and the faculty had grown to five full-time professors and ten part-time instructors, teaching courses with titles such as Bills and Notes, Domestic Relations, Moot Court, and Contracts.

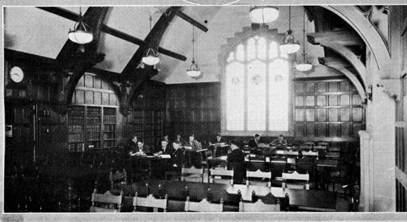

On August 27, 1924, a new $200,000 Law Building was dedicated on the site of the Mackie Mansion. The Law School now had a home of its own. According to a June 1924 Marquette Law Review article, the Law Building—later to be renamed Sensenbrenner Hall—was the “earnest desire of our dean and every student and alumnus.” Features of the building included “four large lecture rooms and a large Moot Court room” and a “third floor [to] be occupied entirely by the library capable of holding 50,000 volumes.” The third-floor reading room, then known as Grimmelsman Memorial Hall (immediately below), was described in the December 1924 issue of the Marquette Law Review as similar in design to “the old Hall of the Middle Temple, Inns of Court, and other collegiate buildings in England.”

This “magnificent structure of Gothic design” (as the 1925 Marquette University yearbook, Hilltop, described the new building) would anchor the eastern edge of Marquette’s academic campus for the next 86 years. Well into the twenty-first century, Marquette law students reaped the benefits of a legal education taught by expert faculty, no matter the age or size of the structure. Yet an institution does not advance without change, and changes were abundant starting in the 1960s. A 1967 addition to Sensenbrenner Hall provided a new library, the Legal Research Center (below left). Another building expansion in the 1980s increased classroom, library, and office space.

Expansion occurred as well in the number of course offerings. In 1968, the Law School offered 44 courses, only slightly more than the 32 courses offered in 1908. By 1988, the number of courses offered had more than doubled to 96. Technology advances over the next two decades brought laptop computers, online research, and a faculty blog to the everyday world of Marquette Law School, while course titles such as Internet Law and E-Discovery reflected the changes in both the legal profession and the larger society.

More changes were on the horizon. By 2005, University and Law School officials agreed that Sensenbrenner Hall, even with additions and renovations, could no longer provide students and faculty with the physical plant required for a premier law school. A new facility would be built, with an exterior design that would be, in the words of Dean Joseph D. Kearney, “noble, bold, harmonious, dramatic, confident, slightly willful, and, in a word, great” and an exterior that would be “open to the community” and “conducive to a sense of community.”

On a perfect autumn afternoon, Wednesday, September 8, 2010, some 1,600 Law School faculty, donors, students, alumni, friends, and Marquette colleagues gathered to participate in the dedication of Ray and Kay Eckstein Hall, the Law School’s new home. Opening remarks were given by Chief Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, United States Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia gave the keynote address, and Archbishop Timothy M. Dolan of New York, along with Archbishop Jerome E. Listecki of Milwaukee, blessed the new building. Dean Kearney hailed Rev. Robert A. Wild, S.J., President of the University, as the person most responsible for the new building, together with Ray and Kay Eckstein, also present.

The light-filled and spacious structure features twelve classrooms, eight conference/seminar rooms, numerous group-study rooms, two courtrooms, faculty suites and offices, a two-story reading room, a conference center, café, fitness center, chapel, two fireplaces, two levels of underground parking, and a library that merges seamlessly into the rest of the program on all four floors. Within its first year, Eckstein Hall welcomed several thousand visitors and guests from the region to lectures, debates, town-hall meetings, conferences, and library research—in the words of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, “becoming Milwaukee’s public square, where people of different political views can come together and hash out the issues of the day.”

Most importantly, students have settled into the new building that they now call home. Even with all the glass and light and space, these current students—not unlike their predecessors almost a century ago—know that reading is at the heart of their legal education. In the “magnificent structure” of 1924, much praise was given to the third-floor library and reading room. In Eckstein Hall, reading takes place in small group-study rooms and the open Huiras Lounge outside the dean’s office on the second floor, in the silence of the Aitken Reading Room (photo above), in the comfort of the fourth-floor gallery overlooking the Marquette interchange—and in many other places as well. Reading forms the essence of legal education. Essential, too, to both that education and the human spirit are the relationships that future Marquette lawyers form with one another during their time in Eckstein Hall.